Navigating the Unknown: The Indispensable Role of Native American Guides in Early Exploration

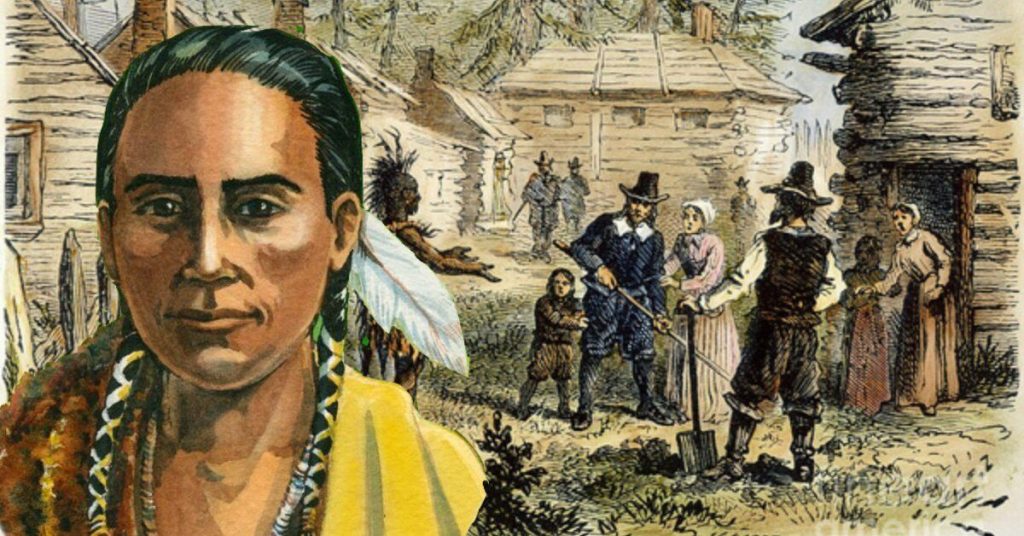

Before the advent of satellite imagery, GPS, or even reliable maps, vast swathes of North America remained a terra incognita to European and Euro-American explorers. Towering mountain ranges, impenetrable forests, sprawling deserts, and an intricate web of rivers and lakes presented an overwhelming challenge to those venturing into the continent’s interior. For these ambitious, often naive, and frequently ill-prepared expeditions, success – and indeed, survival – hinged almost entirely on the knowledge, skills, and diplomatic prowess of one crucial, often unsung, group: Native American guides. Their role transcended mere pathfinding; they were interpreters, diplomats, providers, teachers, and cultural bridges, without whom the narrative of North American exploration would be drastically different, if it existed at all.

The very concept of "exploration" in a land already inhabited for millennia is inherently colonial, yet it underscores the profound chasm in understanding between the newcomers and the Indigenous peoples. While Europeans arrived with compasses and chronometers, they lacked the fundamental understanding of the land itself – its seasonal rhythms, its hidden dangers, its resources, and its human geography. Native Americans, on the other hand, possessed an encyclopedic knowledge passed down through generations, honed by intimate interaction with their environment. They knew the safest routes through treacherous terrain, the locations of potable water in arid regions, the edible and medicinal properties of plants, and the behavior of local wildlife. This knowledge was not merely theoretical; it was the foundation of their very existence.

One of the most critical functions of Native American guides was, naturally, navigation and pathfinding. European explorers, often following outdated maps or vague rumors, would have been hopelessly lost without local expertise. Imagine the Lewis and Clark expedition, tasked with charting a route to the Pacific Ocean across an immense and diverse landscape. While Meriwether Lewis and William Clark were skilled cartographers and outdoorsmen, they were entirely reliant on Indigenous knowledge to traverse the Missouri River’s complex tributaries, cross the formidable Rocky Mountains, and understand the flow of the Columbia River. Their journals are replete with instances where Native American advice, often from individuals like Sacagawea of the Lemhi Shoshone, dictated their route, saved them from starvation, or led them to crucial supplies. Sacagawea, though not a traditional "guide" in the sense of leading a trail, was an invaluable asset, identifying edible plants, finding game, and most importantly, acting as an interpreter and a symbol of peace. Clark, in particular, frequently noted her calming influence and the trust she inspired among other tribes.

Beyond mere topography, these guides offered vital insights into the "human geography" of the continent. North America was a mosaic of hundreds of distinct Indigenous nations, each with its own language, customs, political alliances, and territorial claims. Navigating this intricate web of human relations was often more perilous than any natural obstacle. Native American guides served as crucial cultural mediators and interpreters, translating not just words but also complex social protocols and diplomatic nuances. They could discern friend from foe, advise on appropriate gifts and greetings, and prevent misunderstandings that could easily escalate into conflict. The presence of Indigenous women and children, often accompanying these guides, was particularly significant. As historian James P. Ronda notes regarding Sacagawea’s role, "Her presence announced to every Indian she met that this was not a war party." It conveyed an intention of peace and commerce, allowing the explorers to engage with tribes who might otherwise have viewed them as a threat.

The skills of these guides extended far beyond language and direction. They were masters of survival in the harshest environments. For expeditions facing dwindling supplies and the constant threat of starvation, Indigenous guides were often the primary source of sustenance. They were expert hunters, trackers, and foragers, able to locate game where Europeans saw none, and identify a vast array of edible roots, berries, and medicinal plants. They taught explorers how to build shelters suited to local conditions, how to make fire in adverse weather, and how to prepare and preserve food in ways unknown to the newcomers. When Lewis and Clark faced starvation in the Bitterroot Mountains, it was the Nez Perce who provided them with food and critical knowledge, saving the expedition from collapse. This transfer of knowledge was not a one-way street; while explorers gained invaluable practical skills, Indigenous communities also learned about European technologies, trade goods, and political structures, though often to their detriment in the long run.

The role of Native American guides predates and extends far beyond the well-documented Lewis and Clark expedition. From the earliest Spanish forays into the American Southwest in the 16th century, Indigenous peoples were essential. Estevanico, an enslaved African man, was a pivotal guide for Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca’s journey across the continent, learning multiple Indigenous languages and navigating complex tribal territories. Later, the French fur traders, the coureurs des bois, formed deep relationships with various Indigenous nations, relying on them for guidance through the Great Lakes and Mississippi River systems, learning their languages, and adopting their survival techniques. Figures like La Salle and Marquette depended heavily on Algonquin and Illinois guides for their explorations of the Mississippi.

In the 19th century, as the United States pushed westward, Native American guides continued to be indispensable. John C. Frémont, often celebrated as "The Pathfinder," relied heavily on Shoshone, Delaware, and other Indigenous guides and scouts, though his official reports often minimized their contributions in favor of his own heroic narrative. The infamous "Donner Party," a group of American pioneers, tragically perished in the Sierra Nevada mountains after disregarding the advice of local Washoe guides who warned against a supposedly "shorter" route. This stark example underscores the dire consequences of ignoring Indigenous wisdom.

However, the relationship between explorers and their Indigenous guides was often fraught with complexities and contradictions. While indispensable, guides were frequently underpaid, exploited, and their knowledge taken for granted. Their contributions were often downplayed or erased from official accounts, reflecting the prevailing racist attitudes of the era. The very act of guiding explorers into new territories sometimes inadvertently paved the way for future displacement, conflict, and the destruction of Indigenous ways of life. Guides like Sacagawea, while celebrated today, faced immense personal challenges and lived in a world rapidly changing due to the very expeditions they facilitated.

Ultimately, the story of North American exploration is incomplete and profoundly misleading without acknowledging the central role of Native American guides. They were not merely passive assistants but active agents, crucial decision-makers, and often the difference between success and catastrophic failure. Their intimate connection to the land, their deep cultural understanding, and their unparalleled survival skills were the true compasses that guided European and Euro-American expeditions through the vast, formidable, and beautiful continent. To truly understand the history of exploration in North America is to recognize the footprints of these Indigenous pathfinders, whose wisdom and courage helped to chart the course of a nation, even as it irrevocably altered their own. Their legacy serves as a powerful reminder of the invaluable knowledge held by Indigenous peoples and the profound, yet often overlooked, collaborations that shaped the course of history.