The Vanished Land Bridge: Unraveling the Epic Journey to the Americas

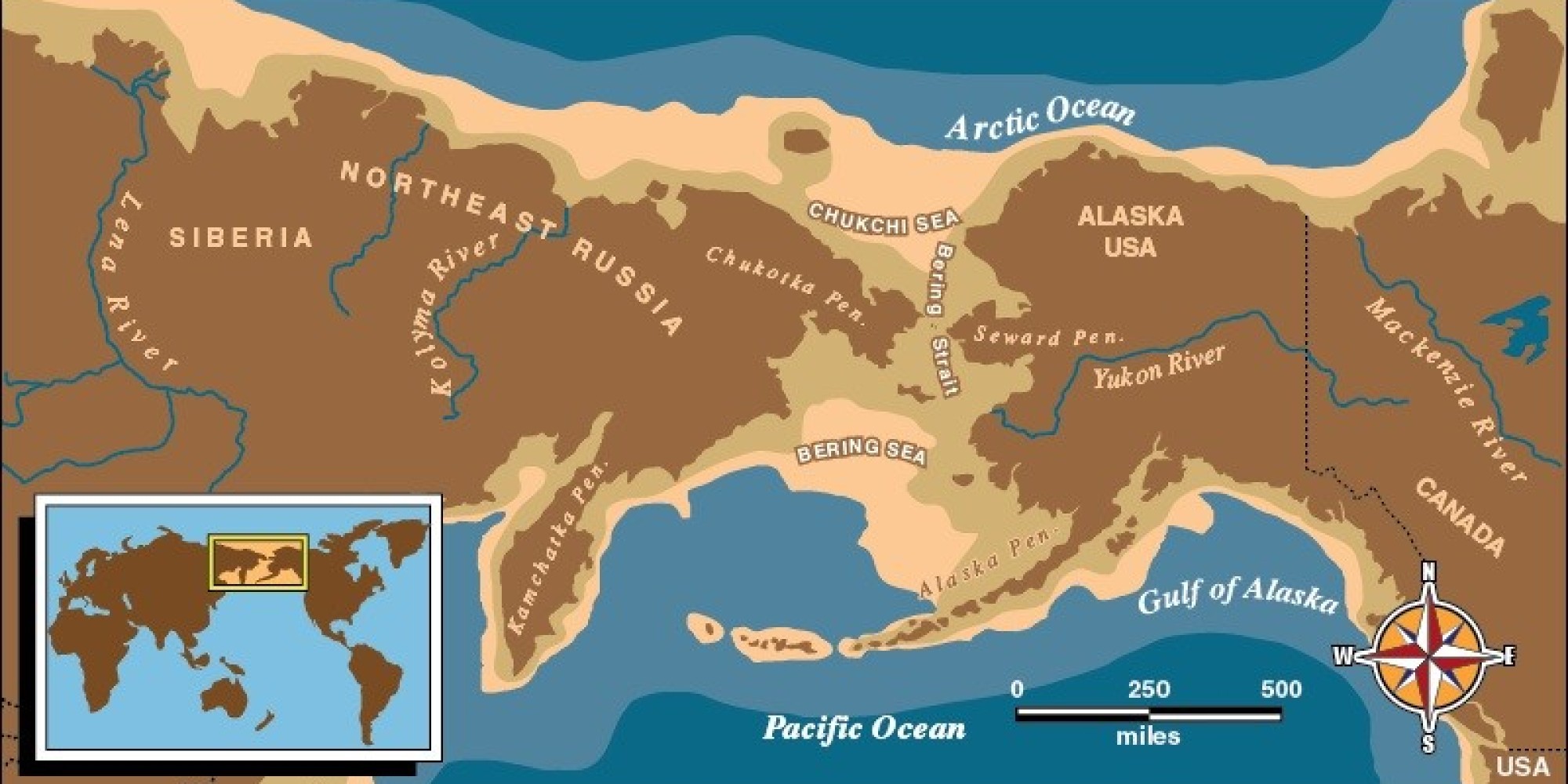

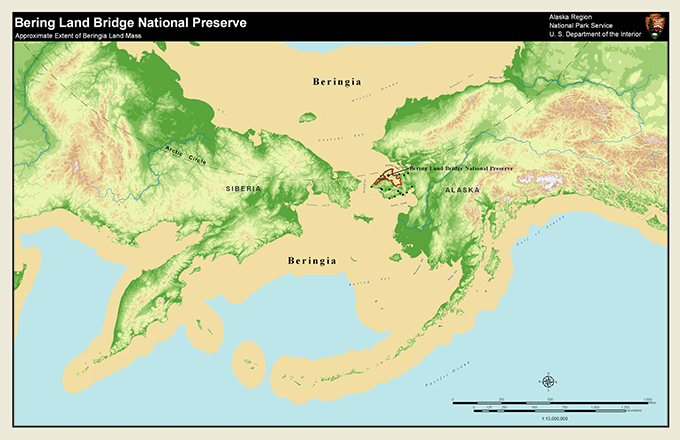

The Americas, vast and diverse, were once an empty canvas, untouched by human footsteps. Today, from the frozen tundras of the Arctic to the southernmost tip of Patagonia, the continents teem with life and culture, a testament to an epic journey that began tens of thousands of years ago. The prevailing scientific narrative for this incredible peopling of the New World centers on a phenomenon known as the Bering Land Bridge – a colossal, now-submerged landmass that once connected Asia to North America. Far from a simple crossing, this vanished continent, known as Beringia, was a vibrant ecosystem, a crucible of human adaptation, and the gateway to a hemisphere.

The story of the Bering Land Bridge theory is one of persistent inquiry, fueled by a compelling mystery: how did humans first arrive in the Americas? For centuries, various myths and theories circulated, from lost tribes of Israel to spontaneous generation. However, as the scientific method gained traction, observations began to point towards a more plausible explanation. Early European explorers and naturalists noted striking similarities between the flora and fauna of Siberia and Alaska, suggesting a past geographical connection. Furthermore, the physical appearance and genetic markers of Indigenous peoples across the Americas often bore resemblances to East Asian populations, reinforcing the idea of an Asian origin.

The Genesis of a Theory: From Speculation to Scientific Consensus

The formal conceptualization of a land bridge emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Geologists studying the Earth’s ice ages realized that during periods of extensive glaciation, vast quantities of ocean water would have been locked up in continental ice sheets, leading to a significant drop in global sea levels. This drop, sometimes exceeding 100 meters, would have exposed shallow continental shelves, particularly in the Bering Strait region.

One of the earliest proponents of a land bridge for human migration was American paleontologist William Healey Dall in the 1870s, though his focus was primarily on animal migrations. It was the Austrian-American geologist and paleontologist Charles Schuchert who, in 1910, provided a more detailed geological argument for the existence of a "Bering land bridge" during glacial periods, specifically linking it to human entry into North America. His work, alongside that of other pioneering scientists, laid the groundwork for what would become the dominant theory of the peopling of the Americas.

By the mid-20th century, with a better understanding of glacial cycles and sea-level fluctuations, the Bering Land Bridge theory solidified into mainstream scientific thought. It posited that during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), roughly 26,500 to 19,000 years ago, a massive landmass emerged, extending thousands of kilometers from north to south and east to west, linking what is now eastern Siberia and western Alaska. This wasn’t merely a narrow strip of land; it was a subcontinental region – Beringia – an expansive, ice-free, grassy steppe-tundra environment, teeming with megafauna such as woolly mammoths, steppe bison, horses, and caribou.

Archaeological Echoes: Tracing Ancient Footprints

The most direct evidence for human presence and migration across Beringia comes from archaeology. For decades, the "Clovis First" hypothesis dominated, suggesting that the Clovis culture, characterized by distinctive fluted projectile points, represented the earliest human inhabitants of the Americas, arriving around 13,000 years ago via an ice-free corridor that opened up in present-day Canada. However, this view has been significantly challenged and largely superseded by discoveries of "Pre-Clovis" sites.

Perhaps the most compelling of these is Monte Verde in Chile, excavated by archaeologist Tom Dillehay. Radiocarbon dating places human occupation there at around 14,500 years ago, pushing back the arrival date of humans in the Americas by over a millennium. This was a critical discovery because it indicated humans were in South America before the traditional timing for the opening of the ice-free corridor, implying either an earlier, unknown route or a coastal migration. Other significant Pre-Clovis sites, such as Paisley Caves in Oregon (with human coprolites dating to ~14,300 years ago) and Meadowcroft Rockshelter in Pennsylvania (~16,000 years ago), further cemented the idea of an earlier presence.

From the Asian side, archaeological sites in Siberia, such as Yana RHS (Rhinoceros Horn Site), have yielded evidence of human occupation dating back as far as 32,000 years ago, showing that humans were well-established in Northeast Asia before the peak of the LGM, making them prime candidates for the Beringian crossing. These sites provide a crucial link, showing a continuum of human presence leading up to the land bridge.

The Genetic Blueprint: Stories in Our DNA

Genetic research has revolutionized our understanding of the peopling of the Americas, providing an independent line of evidence that largely corroborates and refines the Bering Land Bridge theory. Studies of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), passed down exclusively from mother to child, and Y-chromosome DNA, passed from father to son, have identified specific haplogroups (genetic lineages) – A, B, C, D, and X – that are characteristic of Indigenous American populations.

Crucially, these haplogroups are also found in East Asian and Siberian populations, forming a clear genetic bridge. Geneticists have observed what is known as a "founder effect" – a reduction in genetic diversity among Native Americans compared to their Asian ancestors, consistent with a relatively small founding population that migrated across Beringia.

One of the most fascinating genetic insights is the "Beringian Standstill" hypothesis. This theory, supported by a growing body of genetic evidence, suggests that the initial human migrants didn’t just walk straight across the land bridge. Instead, a relatively small population became isolated in Beringia for several millennia – perhaps between 15,000 to 25,000 years ago – during the LGM when massive ice sheets blocked further movement south. During this period, genetic mutations accumulated, leading to the distinct haplogroups observed in Native Americans today. This extended period of isolation in Beringia would have allowed for significant cultural and biological adaptation to the unique Arctic-steppe environment before the final push into the unglaciated Americas. As renowned geneticist Eske Willerslev noted, "Beringia was not just a bridge, but a homeland for thousands of years."

Geological and Paleoenvironmental Clues: Reconstructing a Lost World

Beyond archaeological finds and genetic blueprints, geological and paleoenvironmental evidence provides the physical context for Beringia. Scientists use bathymetric maps (showing the contours of the ocean floor) to reconstruct the extent of the land bridge based on past sea levels. Core samples drilled from the ocean floor contain layers of sediment and microfossils (like pollen and diatoms) that reveal the ancient environment of Beringia. These samples confirm that during glacial periods, the Bering Strait region was indeed dry land and supported a steppe-tundra ecosystem, distinct from the boreal forests found today.

The presence of ancient peat bogs and permafrost features within these cores further supports the idea of a stable, long-lasting landmass. Furthermore, studies of ancient shorelines and isostatic rebound (the rising of landmasses after the removal of glacial ice) provide additional data points that help reconstruct the timing and extent of Beringia’s emergence and submergence.

Evolving Narratives: The Coastal Migration and Beyond

While the Bering Land Bridge remains central, the understanding of how and when people moved from Beringia into the wider Americas has evolved significantly. The "ice-free corridor" that was once thought to be the sole route south through the interior of North America is now seen as problematic. Research suggests this corridor, a narrow passage between the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets, didn’t become fully viable for human passage until around 13,000 years ago, which clashes with the earlier dates from Pre-Clovis sites like Monte Verde.

This discrepancy has given rise to the "Coastal Migration Hypothesis," often dubbed the "Kelp Highway." This theory proposes that early migrants, adapted to maritime environments, traveled along the Pacific coast of Beringia and North America, using boats or walking along exposed coastlines. The rich marine ecosystems, particularly kelp forests, would have provided abundant food resources, making such a journey feasible even when the interior was blocked by ice. Archaeological evidence from islands and coastal sites in Alaska and British Columbia, though challenging to find due to rising sea levels, supports this idea, with some sites yielding tools and artifacts indicative of a coastal adaptation.

Conclusion: A Dynamic Story of Human Resilience

The Bering Land Bridge theory, far from being static, is a dynamic and evolving narrative, continuously refined by new archaeological discoveries, sophisticated genetic analyses, and advanced geological modeling. It tells a profound story not just of geography, but of human resilience, adaptability, and the relentless drive to explore.

From the initial conceptualization of a lost landmass to the intricate details of a "Beringian Standstill" and the "Kelp Highway," the scientific community continues to piece together this monumental chapter in human history. The vanished land bridge was more than just a path; it was a world unto itself, a crucial stage in the epic journey that populated two continents and laid the foundations for the rich tapestry of Indigenous cultures we see today. As technology advances and new sites are uncovered, the mysteries of Beringia will undoubtedly continue to yield even more astonishing insights into our shared past.