Echoes in the Earth: Unearthing North America’s Ancient Civilizations

For centuries, a pervasive myth painted North America as a vast, untamed wilderness, sparsely populated by nomadic tribes, awaiting the arrival of European "discovery." This narrative, steeped in colonial ambition, conveniently overlooked a profound truth: long before the Nina, Pinta, and Santa Maria set sail, the continent teemed with vibrant, complex civilizations. From sophisticated urban centers to monumental earthworks, from ingenious agricultural systems to intricate trade networks, ancient Native American societies carved out empires and cultures that rivaled, and in some aspects surpassed, their Old World contemporaries. Their stories, etched into the landscape and whispered through generations, are now being rediscovered, revealing a rich tapestry of innovation, spirituality, and resilience that fundamentally reshapes our understanding of American history.

The journey into this pre-Columbian past begins not with cities, but with the first intrepid pioneers who ventured into an Ice Age continent. Around 13,000 years ago, the Clovis culture emerged, named for the distinctive fluted projectile points found near Clovis, New Mexico. These highly skilled big-game hunters, armed with their iconic spear points, roamed a landscape teeming with megafauna – mammoths, mastodons, and saber-toothed cats. For decades, Clovis was considered the earliest culture in the Americas, the vanguard of humanity’s expansion. However, archaeological breakthroughs at sites like Monte Verde in Chile and Buttermilk Creek in Texas have pushed back the timeline significantly, suggesting human presence possibly as early as 20,000 to 30,000 years ago, opening fascinating new chapters in the story of human migration and adaptation. These "Pre-Clovis" peoples adapted to diverse environments, laying the groundwork for the extraordinary cultural diversification that would follow.

As the glaciers retreated and the climate warmed, the Archaic Period (roughly 8,000 BCE to 1,000 BCE) saw Native American societies transition from nomadic megafauna hunting to a more diversified subsistence strategy. This era was characterized by regional specialization: coastal communities harnessed marine resources, desert dwellers became experts in foraging hardy plants, and forest inhabitants utilized a wide array of nuts, berries, and smaller game. Crucially, this period also witnessed the nascent stages of agriculture. Early cultivation of native plants like squash, gourds, and sunflowers began to take root, slowly paving the way for more sedentary lifestyles and the eventual rise of larger, more complex societies. The seeds of civilization were literally being sown.

Perhaps nowhere is the sheer scale and ingenuity of ancient North American cultures more evident than in the traditions of the Mound Builders. Spanning millennia and encompassing diverse groups, these societies sculpted the earth into monumental testaments to their beliefs and social structures. The Adena culture (c. 1000 BCE – 200 CE), centered in the Ohio River Valley, initiated this tradition with conical burial mounds, often containing elaborate grave goods that hint at early social stratification and spiritual practices. These mounds were not merely graves; they were sacred spaces, focal points for community and ceremony, carefully aligned with celestial events.

Building upon this foundation, the Hopewell culture (c. 200 BCE – 500 CE) exploded across the eastern woodlands, creating some of the most spectacular earthworks in the world. Their influence stretched from the Great Lakes to the Gulf Coast, connected by an astonishing trade network that moved exotic materials like obsidian from the Rocky Mountains, copper from Lake Superior, and conch shells from the Atlantic. Hopewell sites, such as Newark Earthworks and Mound City in Ohio, feature colossal geometric enclosures – perfect circles, squares, and octagons – often spanning hundreds of acres, whose precision suggests advanced mathematical and astronomical knowledge. "These earthworks are not just piles of dirt," notes archaeologist Dr. N. Scott Momaday, "they are monumental statements, expressing a profound connection to the cosmos and the landscape." The iconic Great Serpent Mound in Ohio, an effigy mound winding over a quarter-mile, remains a breathtaking example of their artistic and spiritual vision.

The apex of mound-building cultures arrived with the Mississippian culture (c. 800 CE – 1600 CE). Fueled by the intensive cultivation of maize (corn) and beans, this civilization gave rise to sprawling urban centers and powerful chiefdoms across the American Midwest and Southeast. The undisputed jewel of the Mississippian world was Cahokia, located near modern-day St. Louis. At its peak around 1050-1200 CE, Cahokia was larger than London at the same time, boasting a population estimated between 10,000 and 20,000 people, with surrounding communities pushing that figure higher. Its central feature, Monk’s Mound, is a colossal earthen platform mound, larger at its base than the Great Pyramid of Giza, supporting a massive temple or chief’s residence. Cahokia was a sophisticated, planned city with plazas, residential areas, and even a large timber circle ("Woodhenge") used for astronomical observations. This was a true metropolis, a bustling hub of trade, religion, and political power, demonstrating a level of social organization and engineering prowess previously thought exclusive to the Old World.

While the Mississippians dominated the fertile river valleys, another distinct and equally advanced civilization flourished in the arid Southwest: the Ancestral Puebloans (often referred to as Anasazi, a Navajo word meaning "ancient enemies" or "ancestors of our enemies," though "Ancestral Puebloans" is now preferred by many). Evolving from earlier Basketmaker traditions, these ingenious people mastered dryland agriculture and architectural innovation in the challenging Four Corners region of present-day Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah. Their story is one of adapting to extremes, developing sophisticated water harvesting techniques and constructing monumental structures that defy belief.

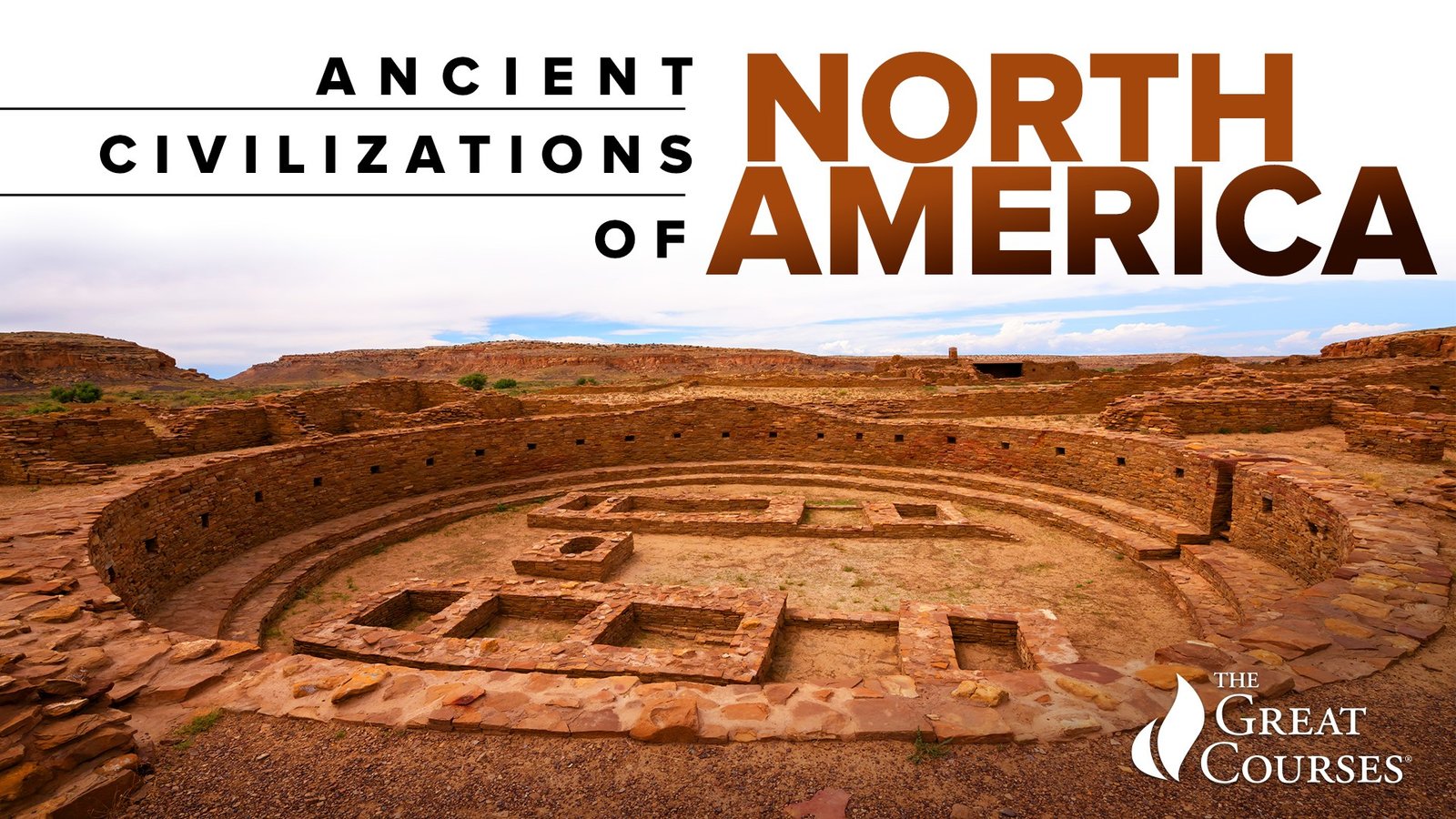

The cultural zenith of the Ancestral Puebloans is perhaps best exemplified by Chaco Canyon in New Mexico (c. 850-1250 CE). Here, amidst a harsh desert landscape, they built "Great Houses" like Pueblo Bonito, a massive D-shaped structure with hundreds of rooms, soaring multi-stories high. These structures were meticulously aligned with celestial events and connected by an extensive network of straight roads, some extending for dozens of miles, even over difficult terrain – roads that baffled early European explorers. Chaco was not merely a residential hub; it was a ceremonial, economic, and astronomical center, radiating influence across the region. As environmental pressures mounted, Ancestral Puebloans began migrating, leading to the construction of awe-inspiring cliff dwellings at sites like Mesa Verde in Colorado. Perched precariously in natural alcoves, these architectural marvels offered protection and efficient use of space, reflecting a remarkable blend of ingenuity and spiritual reverence. "To stand in a kiva at Mesa Verde," observed author Willa Cather, "is to feel the presence of a people who lived in profound harmony with their world."

Beyond these monumental civilizations, countless other complex societies thrived. The Hohokam in present-day Arizona developed an intricate network of irrigation canals, some extending for miles, transforming the desert into fertile farmlands. The Iroquois Confederacy in the Northeast forged a sophisticated political alliance of five (later six) nations, whose democratic principles and federal structure would later influence the framers of the United States Constitution. Along the Pacific Northwest coast, rich marine resources fostered cultures characterized by elaborate social hierarchies, distinctive art (such as totem poles), and advanced woodworking.

The eventual decline or transformation of many of these ancient civilizations – Cahokia’s abandonment, the Ancestral Puebloan migrations – were often complex processes driven by a combination of environmental degradation (drought, deforestation), internal social or political strife, and shifting trade routes. These were not "failures" but rather adaptations and evolutions, leading to the diverse and resilient Native American nations encountered by Europeans.

The rediscovery of these ancient North American civilizations is more than just an academic exercise; it is a profound re-evaluation of history itself. It challenges the colonial narrative of an empty land awaiting "progress" and replaces it with a vibrant, dynamic picture of human achievement, innovation, and deep connection to the land. As archaeologists continue to uncover new evidence and as indigenous voices increasingly share their ancestral knowledge, the echoes of these magnificent societies grow clearer, reminding us that North America has a history far richer, far older, and far more complex than many have ever dared to imagine. Their legacy is not buried, but interwoven into the very fabric of the continent, waiting for us to listen, learn, and respectfully acknowledge the enduring brilliance of those who came before.