The Enduring Struggle: Tribal Sovereignty and its Legal Labyrinth in the United States

Indigenous nations within the United States are not mere ethnic groups; they are sovereign governmental entities with a unique political status, a reality often misunderstood and perpetually challenged. Their inherent right to self-governance, predating the formation of the United States, has been a battleground of legal interpretation, legislative action, and judicial rulings for centuries. The journey of tribal sovereignty is a complex tapestry woven with threads of broken treaties, landmark court decisions, legislative victories, and ongoing struggles for self-determination against a backdrop of federal "plenary power."

At its heart, tribal sovereignty is the right of Native American tribes to govern themselves, manage their lands, and regulate their internal affairs. This is not a right granted by the United States but an inherent power that predates European contact. As the Supreme Court affirmed in the seminal "Marshall Trilogy" cases of the 1820s and 1830s, particularly Worcester v. Georgia (1832), tribal nations are distinct political communities, retaining their original natural rights, though Justice John Marshall famously described them as "domestic dependent nations" – a phrase that encapsulates both their distinctness and their subordinate relationship to the federal government. This paradoxical status has defined the legal landscape for Native Americans ever since.

A History of Shifting Sands: Treaties and Trust Responsibility

The early relationship between European powers and Native American tribes was largely one of nation-to-nation diplomacy, formalized through treaties. These agreements, often negotiated under duress, recognized tribal land ownership and self-governance in exchange for vast land cessions. However, as American expansionism gained momentum, these treaties were routinely violated, reinterpreted, or abrogated, leading to forced removals, land loss, and the erosion of tribal authority.

The concept of the "trust responsibility" emerged from this history. It posits that the federal government has a legal and moral obligation to protect tribal lands, assets, resources, and treaty rights, and to provide services necessary for tribal self-governance and well-being. While often framed as a protective measure, the trust responsibility has also been a double-edged sword, used by the federal government to justify paternalistic oversight and control over tribal affairs, limiting true self-determination.

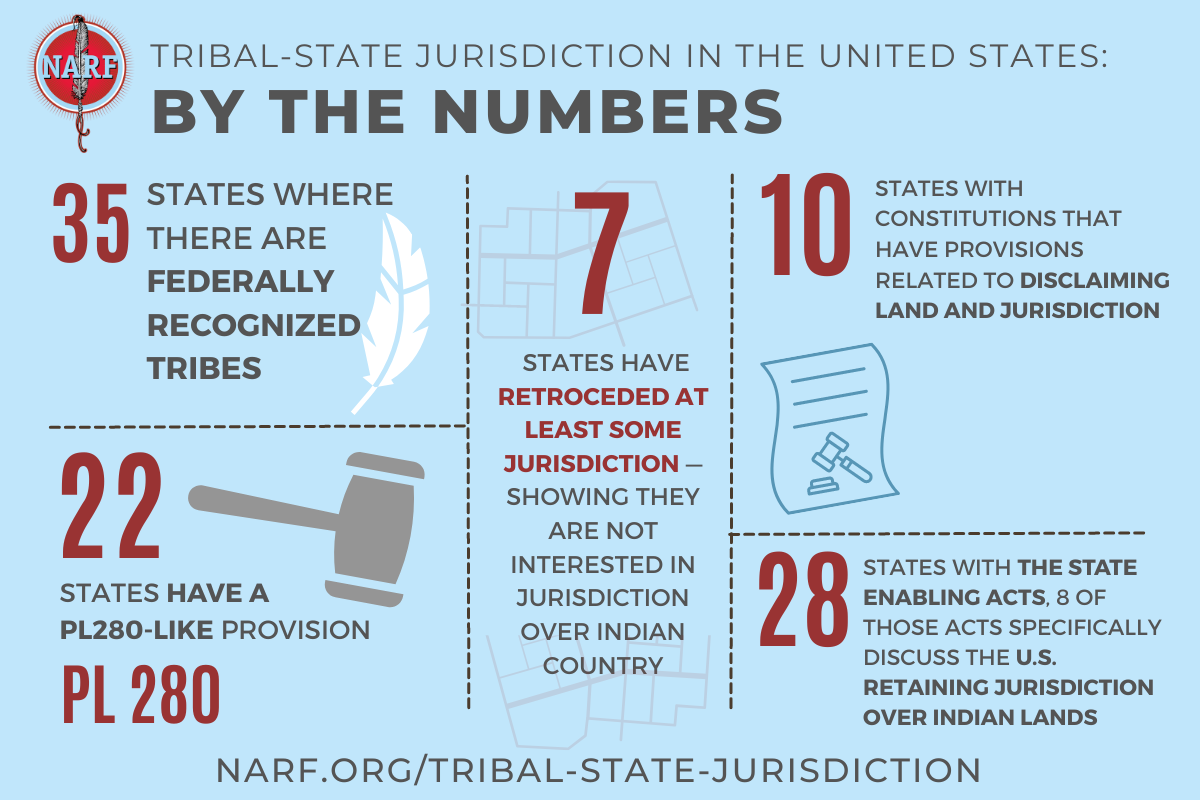

Jurisdiction: The Constant Battleground

Perhaps no area of tribal sovereignty is as complex and contested as jurisdiction. Who has the authority to make and enforce laws on tribal lands? The answer is far from straightforward and depends on the nature of the crime or civil dispute, the identity of the parties involved (Native or non-Native), and the specific history of the reservation.

For decades, tribes largely exercised criminal jurisdiction over their own members. However, the landmark Supreme Court case Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe (1978) stripped tribes of criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians on their reservations, reasoning that such power had been implicitly divested. This decision created a "jurisdictional vacuum," as state governments generally lacked authority on tribal lands, and federal law enforcement often proved inadequate, particularly for misdemeanor crimes. The result was a significant rise in crime rates, especially violence against Native women, who became vulnerable targets due to the inability of tribal courts to prosecute non-Native offenders.

Congress attempted to address this in part with the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) reauthorization in 2013, which restored some tribal criminal jurisdiction over non-Native perpetrators of domestic violence, dating violence, and violations of protection orders, provided certain due process protections were met. The VAWA reauthorization in 2022 further expanded this "special tribal criminal jurisdiction" to include crimes of sexual assault, stalking, child abuse, and trafficking, representing a significant, albeit partial, restoration of tribal authority.

Civil jurisdiction is equally complex. Generally, tribal courts have jurisdiction over civil matters involving tribal members within reservation boundaries. However, cases involving non-Indians or off-reservation activities often lead to disputes, with federal courts frequently asserting a balancing test that often favors state or federal interests.

Economic Development: A Path to Self-Sufficiency

The exercise of sovereignty is inextricably linked to economic self-sufficiency. For many tribes, the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA) of 1988 proved to be a transformative piece of legislation. It established a framework for tribal governments to operate gaming facilities on reservation lands, provided that states negotiated compacts in good faith. Today, tribal gaming is a multi-billion-dollar industry, generating revenues that tribes use to fund essential government services, infrastructure, healthcare, education, and cultural programs, reducing their reliance on federal appropriations.

However, tribal economies are diversifying far beyond gaming. Many tribes are leveraging their natural resources – energy (oil, gas, wind, solar), timber, agriculture – or investing in tourism, manufacturing, and technology. This economic independence strengthens tribal governance and provides resources to address the systemic challenges faced by their communities. Yet, economic development often brings new legal challenges, particularly concerning taxation, environmental regulation, and the balancing of resource extraction with cultural preservation.

Environmental Protection and Resource Management

Tribal nations hold unique perspectives on environmental stewardship, often rooted in millennia-old cultural traditions that emphasize harmony with nature. Many tribes are at the forefront of the fight against climate change, advocating for sustainable practices and protecting sacred lands and waterways. Legal issues in this arena frequently involve water rights, land use, and the impact of external industrial projects.

The Winters Doctrine (derived from Winters v. United States, 1908) is a cornerstone of tribal water law, establishing that when Congress created reservations, it implicitly reserved sufficient water to fulfill the purposes of those reservations. This doctrine has been crucial for tribes in arid regions, but securing and quantifying these rights often requires lengthy and expensive litigation against states and other water users.

Recent conflicts, such as the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s opposition to the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL), brought the issues of tribal environmental sovereignty and cultural preservation to international attention. The tribe argued that the pipeline threatened their primary water source and desecrated sacred burial grounds, highlighting the tension between national energy interests and tribal treaty rights and environmental protection.

Cultural Preservation and Identity

The legal landscape also plays a vital role in protecting tribal cultures, languages, and identities. The Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) of 1978 is a prime example. Enacted in response to alarmingly high rates of Native American children being removed from their homes and placed into non-Native foster or adoptive families, ICWA established federal standards for the removal and placement of Native children, prioritizing placement with family members or other Native families. This act affirmed tribal sovereignty over their most precious resource: their children and future generations. Despite ongoing legal challenges, most notably Haaland v. Brackeen (2023), the Supreme Court largely upheld ICWA, reaffirming its constitutionality and the plenary power of Congress to legislate in Indian affairs.

Similarly, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) of 1990 requires federal agencies and museums to return Native American human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony to lineal descendants and culturally affiliated Native American tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations. This act acknowledges the deep spiritual and cultural significance of these items and empowers tribes to reclaim their heritage from institutions that often acquired them through unethical means.

The Shadow of Plenary Power

Despite these advancements, the specter of "plenary power" continues to loom large. This doctrine holds that Congress has supreme and exclusive power over Indian affairs, allowing it to abrogate treaties and override tribal self-governance with federal legislation. While modern interpretations suggest this power is not absolute and must be exercised in good faith and for the benefit of tribes (the "trust responsibility"), it remains a significant legal vulnerability for tribal nations. This tension between inherent tribal sovereignty and federal plenary power is the enduring paradox at the heart of U.S. Indian law.

Moving Forward: Resilience and Nation-Building

Today, tribal nations are not merely recipients of federal policy; they are active architects of their own futures. Through persistent advocacy, strategic litigation, and innovative nation-building initiatives, they continue to assert their sovereignty, strengthen their governmental institutions, and address the unique challenges facing their communities. From developing comprehensive legal codes and robust judicial systems to negotiating intergovernmental agreements with states and counties, tribes are demonstrating the practical application of self-determination.

The legal journey of tribal sovereignty is far from over. Issues such as climate change impacts on tribal lands, infrastructure development, digital equity, and the ongoing fight for equitable funding for essential services continue to demand attention. However, the narrative is increasingly one of resilience, resurgence, and the unwavering commitment of tribal nations to govern themselves, protect their cultures, and secure a prosperous future for their people. The United States, in turn, is slowly but surely learning that a true nation-to-nation relationship, founded on respect for inherent sovereignty, is not just a legal obligation but a moral imperative for a just and equitable society.