Guardians of Tomorrow: The Iroquois Nations’ Enduring Environmental Stewardship in New York

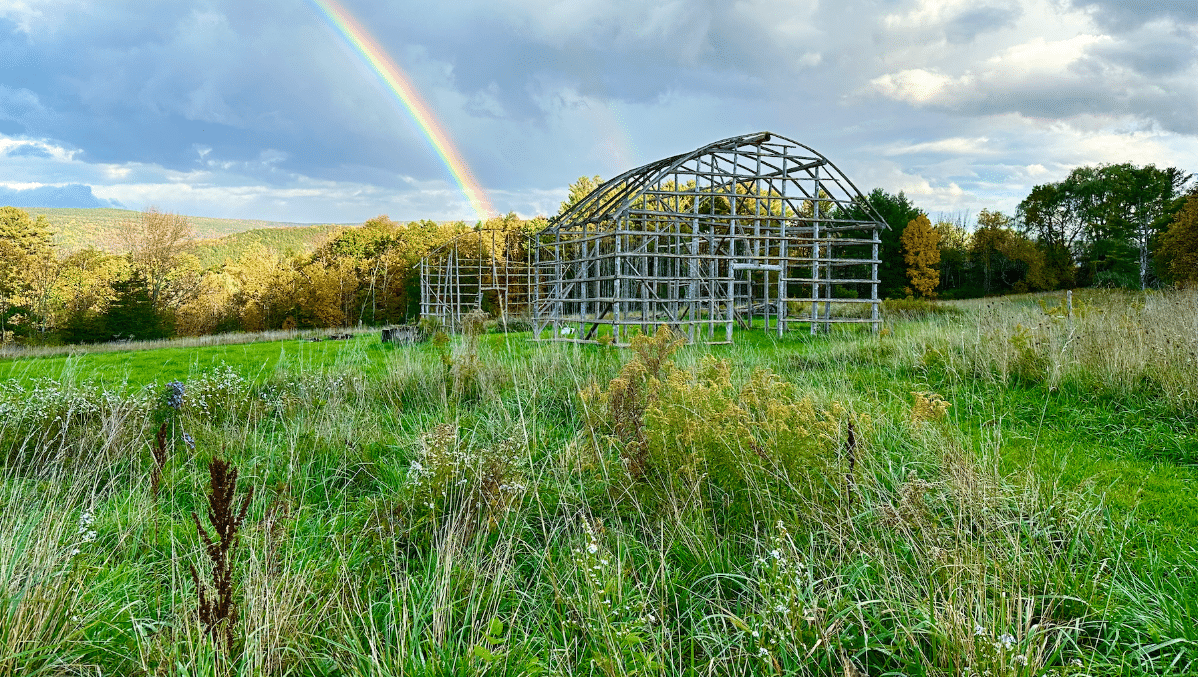

In the verdant landscapes of New York, where ancient forests meet modern cities, a profound environmental narrative is unfolding. It is a story not of recent awakening, but of an enduring commitment to the land and its future, woven into the very fabric of existence by the Iroquois Confederacy, or Haudenosaunee, as they call themselves – the People of the Longhouse. For centuries, long before the concepts of "sustainability" and "conservation" entered mainstream discourse, the Haudenosaunee nations of New York – the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora – have lived by a principle that demands consideration for the next seven generations. Today, this ancient wisdom is not just surviving but thriving, guiding innovative environmental initiatives that offer vital lessons for the entire world.

The Haudenosaunee worldview is fundamentally holistic, perceiving humanity not as separate from nature but as an integral part of an interconnected web of life. This perspective is enshrined in the Great Law of Peace (Kaianere’kó:wa) and articulated powerfully in the Thanksgiving Address (Ohen:ton Karihwatehkwen), a foundational prayer that acknowledges and expresses gratitude for every element of creation, from the smallest blade of grass to the sun, moon, and stars. "In our every deliberation, we must consider the impact of our decisions on the next seven generations," is a maxim often attributed to the Great Peacemaker, the founder of the Confederacy, and it remains the guiding star for contemporary Haudenosaunee environmental efforts.

This deep-rooted philosophy manifests in practical, proactive measures across their ancestral and contemporary territories in New York State. From confronting industrial pollution and restoring vital waterways to embracing renewable energy and revitalizing traditional agriculture, the Iroquois nations are at the forefront of environmental justice and sustainable development.

One of the most pressing environmental challenges faced by Haudenosaunee communities has been the legacy of industrial pollution. The Mohawk Nation at Akwesasne, straddling the U.S. and Canadian borders along the St. Lawrence River, stands as a stark testament to this struggle. Decades of unchecked industrial dumping from nearby aluminum plants (Alcoa) and General Motors facilities left their waters and lands heavily contaminated with PCBs, dioxins, and heavy metals. This environmental assault devastated traditional food sources, impacted community health, and disrupted their way of life.

Yet, Akwesasne has not succumbed to despair. Instead, they have become pioneers in environmental remediation and monitoring. The Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe’s Environment Division works tirelessly to document pollution, advocate for clean-up, and conduct extensive ecological restoration projects. They operate their own environmental testing labs, monitor fish and wildlife, and educate community members on safe consumption practices. "Our elders remember a time when you could drink straight from the river," says Emily Tarbell, an environmental technician at Akwesasne, her voice tinged with a blend of sadness and resolve. "Now, we teach our children not to touch the sediment. But we are fighting to bring that purity back, not just for us, but for everyone downstream." Their advocacy has led to Superfund designations and ongoing, albeit slow, clean-up efforts, demonstrating the power of tribal sovereignty in demanding environmental justice.

Similarly, the Onondaga Nation, the Central Fire of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, has been a leading voice in the campaign to restore Onondaga Lake, once considered one of the most polluted lakes in America. For generations, the lake, sacred to the Onondaga, suffered from industrial waste and municipal sewage. While the clean-up efforts are led by the state and private corporations, the Onondaga Nation has consistently pushed for more comprehensive and culturally appropriate remediation, emphasizing not just chemical reduction but ecological and spiritual restoration. They monitor tributary health, engage in community education, and remind all stakeholders of the lake’s intrinsic value. "The lake is our relative; it needs to be healed, not just capped," asserts Clan Mother Audrey Shenandoah, underscoring the spiritual dimension of their environmental activism.

Beyond remediation, Haudenosaunee nations are actively forging a path towards energy independence and climate resilience. The Seneca Nation, for instance, has invested significantly in renewable energy projects. Their solar array at the Cattaraugus Territory not only powers community buildings but also serves as a visible symbol of their commitment to a sustainable future. The Onondaga Nation has also explored solar power for its facilities, recognizing that reducing reliance on fossil fuels is both an environmental imperative and a step towards greater self-determination.

"For us, energy sovereignty is intertwined with our overall sovereignty," explains Chief Leo Henry of the Seneca Nation. "Controlling our energy means controlling our future. We are investing in technologies that honor the land and air, ensuring that our grandchildren don’t inherit the carbon footprint of past generations." These initiatives are not merely about adopting green technology; they are about aligning modern solutions with ancient values.

Food sovereignty and sustainable agriculture also form a cornerstone of Iroquois environmental initiatives. The traditional "Three Sisters" planting method—corn, beans, and squash—is a prime example of their sophisticated agroecological knowledge. These three crops are planted together in a symbiotic relationship: corn provides a stalk for beans to climb, beans fix nitrogen in the soil, and squash leaves provide ground cover, retaining moisture and deterring weeds. This system enhances soil health, minimizes pest issues, and maximizes yields without chemical inputs.

Today, this knowledge is being revitalized and expanded. Community gardens are flourishing, promoting healthy, traditional diets and addressing issues of food security and chronic diseases that have disproportionately affected Indigenous communities. The Oneida Nation, for example, operates farms that grow traditional crops using organic methods, supplying local community programs and educating members on the importance of reconnecting with their food sources. "Food is medicine, and our traditional foods are our original medicine," states Daniel Homer, an Oneida farmer. "By growing our own, we are not just feeding our bodies; we are nourishing our culture and strengthening our connection to the land." This reconnection extends to teaching youth traditional harvesting, hunting, and fishing practices, ensuring that vital ecological knowledge is passed down.

Land stewardship and biodiversity conservation are also central to Haudenosaunee environmental efforts. The Onondaga Nation meticulously manages its 7,300 acres of reservation land, which, while a mere fraction of their ancestral domain, is treated with utmost reverence. They engage in reforestation, control invasive species, and protect critical habitats for native plants and animals. Their land management practices often blend traditional ecological knowledge with contemporary scientific approaches, creating a powerful model for conservation.

The challenges are immense. Climate change poses threats to traditional lifeways, from unpredictable weather patterns impacting planting seasons to warming waters affecting fish populations. External pressures, including development projects, resource extraction, and continued infringement on treaty rights, persist. Funding for environmental initiatives often remains insufficient, and the scale of historical degradation is daunting.

Despite these obstacles, the spirit of the Haudenosaunee environmental movement remains resolute. Their work is not just about cleaning up pollution or planting trees; it’s about a profound commitment to cultural survival, self-determination, and a vision of a healthy future for all. They consistently remind the broader society that environmental degradation is often a symptom of a deeper spiritual disconnect, a failure to honor the Earth as a living entity.

As the world grapples with escalating environmental crises, the Haudenosaunee nations in New York offer invaluable leadership. Their initiatives demonstrate that effective environmental stewardship is deeply rooted in respect, responsibility, and a long-term vision that transcends immediate gratification. By blending ancient wisdom with modern science, by relentlessly advocating for justice, and by actively working to heal the land, the Iroquois nations are not just protecting their own territories; they are safeguarding the future for the next seven generations and offering a vital blueprint for how all of humanity can become true guardians of tomorrow. Their enduring commitment to the environment serves as a powerful testament to the resilience of Indigenous cultures and a beacon of hope for a sustainable future for New York and beyond.