Echoes of Sovereignty: The Enduring Strength of Ojibwe Tribal Governments in Minnesota

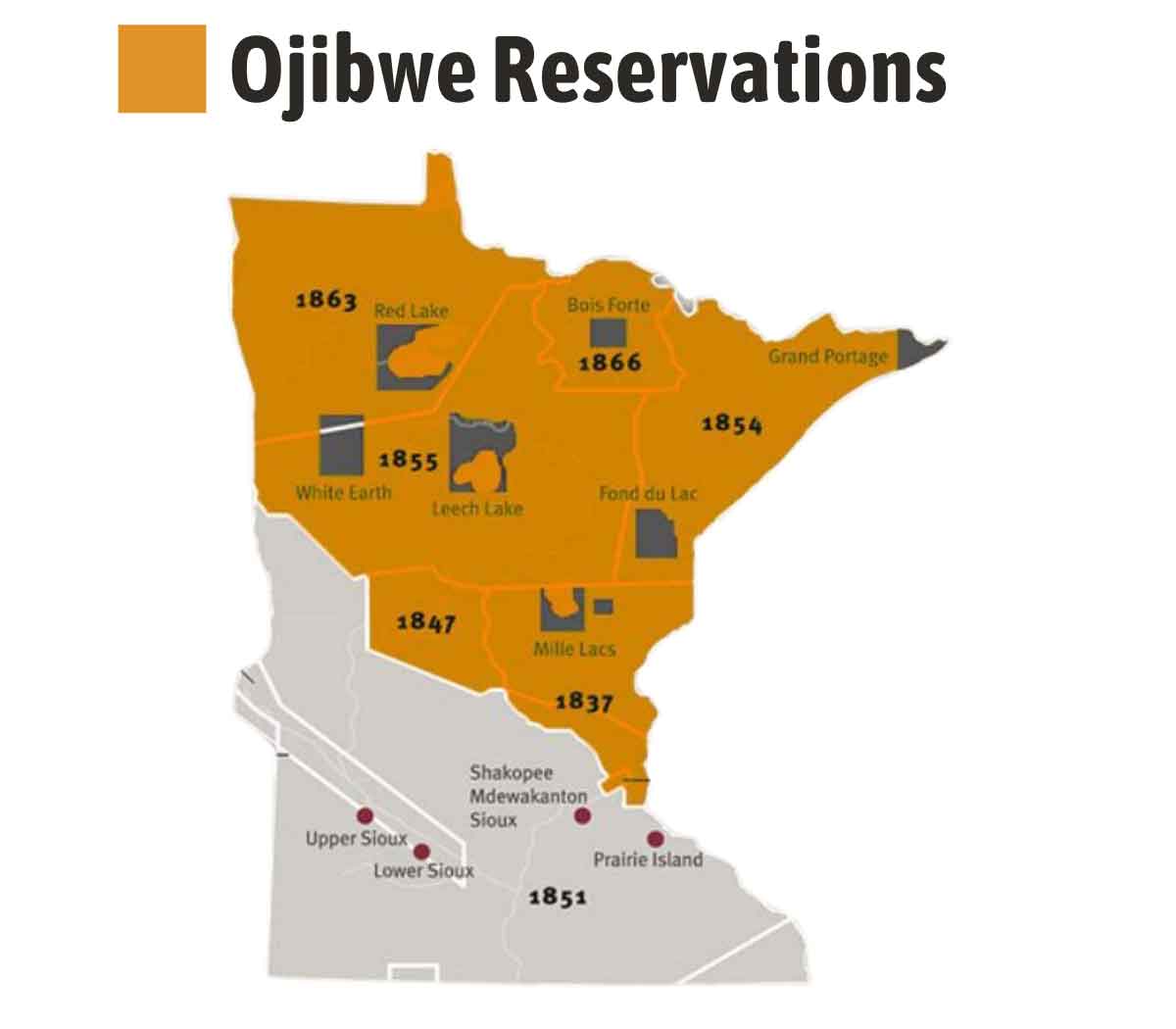

Minnesota, the "Land of 10,000 Lakes," is also home to seven federally recognized Ojibwe (Anishinaabe) tribal nations: the Bois Forte Band of Chippewa, Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, Grand Portage Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe, Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe, Red Lake Nation, and White Earth Nation. These are not merely cultural groups or communities; they are sovereign governments, dynamic political entities with distinct histories, intricate governance structures, and profound impacts on their members, the state of Minnesota, and the broader American landscape. Their journey, marked by resilience through centuries of colonial pressure, assimilation policies, and the unwavering pursuit of self-determination, offers a compelling narrative of enduring sovereignty in the modern era.

A Foundation Forged in History and Treaty Rights

The Ojibwe people have inhabited the Great Lakes region for millennia, developing sophisticated political, economic, and social systems long before European contact. Their traditional governance structures, often decentralized and consensus-based, reflected a deep connection to the land and a communal approach to decision-making. The arrival of European powers, and later the United States, irrevocably altered this landscape, ushering in an era of treaties.

These treaties, often misunderstood as simple land sales, were fundamentally agreements between sovereign nations. The Ojibwe ceded vast territories, including much of present-day Minnesota, in exchange for guaranteed rights to hunt, fish, gather, and live on their remaining lands, as well as promises of services and protection. Crucially, they did not cede their inherent sovereignty. As Dr. Anton Treuer, an Ojibwe language and history scholar, often emphasizes, "The treaties are the supreme law of the land. They are not historical curiosities; they are living documents that define our relationship with the federal government."

The late 19th and early 20th centuries brought an era of devastating federal policies aimed at forced assimilation. The Dawes Act of 1887 broke up communal landholdings into individual allotments, and boarding schools aggressively suppressed Ojibwe language, culture, and traditional governance. This period was designed to dismantle tribal structures and integrate Native Americans into mainstream society, often with tragic consequences for individual identity and collective well-being.

However, the spirit of self-governance persisted. The Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934 marked a turning point, allowing tribes to re-establish formal governments and write constitutions. Most Minnesota Ojibwe bands adopted IRA constitutions, creating elected tribal councils and chairpersons. The Red Lake Nation, however, stands as a unique testament to unwavering sovereignty, having famously rejected the IRA and maintained its own constitution and government, never ceding its land base. This bold decision underscores the diverse paths to modern self-governance among Native nations.

The Architecture of Modern Governance

Today, the seven Ojibwe tribal governments in Minnesota operate much like miniature states within a state, exercising inherent sovereign powers. Each nation has its own constitution (or governing document), elected leadership (typically a tribal council and chairperson), and a robust administrative infrastructure. These governments are responsible for a vast array of public services, mirroring and often exceeding those provided by state and local governments.

- Executive Branch: Led by an elected Chairperson or President, who acts as the chief executive and primary spokesperson for the nation.

- Legislative Branch: Comprised of a Tribal Council, whose members are elected by the tribal citizenry. This council enacts laws, approves budgets, and sets policy.

- Judicial Branch: Many tribes operate their own tribal courts, exercising jurisdiction over tribal members and matters arising on tribal lands. These courts handle civil disputes, family law, and often misdemeanor criminal offenses, reflecting a commitment to justice systems rooted in tribal values. The Fond du Lac Band, for instance, has a highly developed court system, including a Court of Appeals.

- Administrative Departments: Tribal governments manage extensive departments providing essential services:

- Healthcare: Operating clinics, hospitals, and wellness programs, often integrating traditional healing practices with Western medicine. The White Earth Nation, for example, has been a leader in addressing health disparities among its members.

- Education: From early childhood development programs to K-12 schools (like the Bug-O-Nay-Ge-Shig School at Leech Lake) and scholarships for higher education, ensuring cultural relevance in curriculum development.

- Housing: Developing and managing housing projects, offering assistance for repairs, and addressing homelessness.

- Public Safety: Tribal police forces and emergency services ensure the safety and security of their communities.

- Social Services: Providing elder care, child protective services, substance abuse treatment, and family support programs.

- Infrastructure: Building and maintaining roads, utilities, and community facilities.

This comprehensive governmental apparatus is a direct manifestation of sovereignty, allowing tribes to address the unique needs and aspirations of their people, rather than relying solely on external entities.

Economic Self-Sufficiency and Diversification

A cornerstone of modern tribal sovereignty is economic development. For many Ojibwe nations in Minnesota, gaming enterprises have been a significant catalyst for economic growth, providing critical revenue streams to fund essential governmental services and stimulate job creation. Casinos like Grand Casino Mille Lacs and Hinckley (Mille Lacs Band), Black Bear Casino Resort (Fond du Lac Band), and Shooting Star Casino (White Earth Nation) are major employers, not only for tribal members but also for residents of surrounding non-Native communities.

However, tribal governments are keenly aware of the need for diversification. They are strategically investing in a variety of sectors to build sustainable economies:

- Natural Resources: Managing and sustainably utilizing timber, wild rice, and other natural resources within their traditional territories. Wild rice, or Manoomin, is not only an economic asset but also a culturally sacred food source, with tribes actively working to protect its habitats.

- Tourism and Hospitality: Beyond gaming, many tribes operate resorts, cultural centers, and outdoor recreation facilities, drawing visitors to their beautiful lands. Grand Portage, nestled along Lake Superior, leverages its stunning natural beauty and historical significance.

- Retail and Manufacturing: Developing shopping centers, gas stations, and even manufacturing facilities.

- Renewable Energy: Exploring solar and wind energy projects, aligning with traditional values of environmental stewardship.

- Technology: Investing in broadband infrastructure and tech-related businesses to connect and empower their communities in the digital age.

The economic impact of these enterprises extends far beyond reservation borders, contributing hundreds of millions of dollars annually to Minnesota’s economy through wages, purchases, and taxes. As one tribal leader once put it, "Economic sovereignty is the bedrock of self-determination. It allows us to build our own schools, hospitals, and infrastructure, guided by our own values, not by federal appropriations alone."

Cultural Preservation and Language Revitalization

Beyond the tangible services, Ojibwe tribal governments play an indispensable role in preserving and revitalizing their rich culture, language, and traditions. Centuries of assimilation efforts threatened to erase Ojibwemowin (the Ojibwe language), traditional ceremonies, and ancestral knowledge. Today, tribal governments are leading the charge to reverse this trend.

- Language Immersion: Many bands operate or support language immersion programs, from preschools to adult classes, to ensure that Ojibwemowin is passed down to new generations. The White Earth Nation, for example, has been at the forefront of this effort.

- Cultural Centers: Establishing museums, cultural centers, and archives to document and share their history, art, and traditions.

- Traditional Practices: Supporting and facilitating traditional ceremonies, powwows, wild rice harvesting, maple sugaring, and other practices that connect members to their heritage and the land.

- Art and Storytelling: Funding initiatives for Ojibwe artists, musicians, and storytellers to keep cultural expressions vibrant.

This commitment to cultural preservation is not merely nostalgic; it is seen as vital for the identity, well-being, and future strength of the Ojibwe people. It reinforces a sense of belonging and provides a foundation for resilience in the face of ongoing challenges.

Challenges and the Path Forward

Despite their remarkable progress, Ojibwe tribal governments in Minnesota continue to navigate complex challenges. Historical trauma, stemming from generations of injustice, manifests in persistent socioeconomic disparities, including higher rates of poverty, health issues (like diabetes and heart disease), substance abuse, and lower educational attainment compared to the general population.

Jurisdictional complexities remain a constant source of friction. The intricate web of federal, state, and tribal laws often creates ambiguities, particularly concerning law enforcement, taxation, and land use, requiring constant negotiation and advocacy. For example, the status of land "disestablished" by the Supreme Court’s Mille Lacs v. Minnesota decision (which affirmed treaty rights but raised questions about reservation boundaries) continues to be a point of contention for some bands.

Furthermore, balancing traditional values with the demands of modern governance and economic development requires careful deliberation. Decisions about resource management, casino expansion, or educational reforms must always consider their impact on cultural integrity and the long-term well-being of the community.

Yet, the story of Ojibwe tribal governments in Minnesota is overwhelmingly one of strength, adaptation, and an unwavering commitment to self-determination. They are vital partners in Minnesota’s future, contributing to its economic vitality, cultural diversity, and social fabric. Their ongoing work to build robust, self-sufficient nations, while honoring their ancestral traditions, stands as a powerful testament to the enduring spirit of the Anishinaabe people. As sovereign nations within the larger American landscape, they continue to shape their own destinies, ensuring that the echoes of their sovereignty resonate for generations to come.