Sacred Waters, Sovereign Nets: The Enduring Legacy of Ojibwe Fishing in Minnesota

The mist still clings to the surface of Minnesota’s vast lakes as the first rays of dawn pierce the horizon. On the water, a lone figure in a small boat casts a net, a rhythmic motion honed by generations. This isn’t just a scene of quiet industry; it’s a living tableau of resilience, culture, and sovereignty. For the Ojibwe people of Minnesota, fishing is far more than a pastime or a livelihood; it is a profound connection to their heritage, a cornerstone of their identity, and a testament to their enduring treaty rights.

Minnesota, the "Land of 10,000 Lakes," is the ancestral homeland of the Anishinaabeg, or Ojibwe. Their relationship with these waters, teeming with walleye, northern pike, muskie, and whitefish, stretches back millennia. Before the arrival of Europeans, the Ojibwe fished to sustain their communities, employing sophisticated techniques and a deep understanding of the aquatic ecosystem. They were stewards of the land and water, their practices guided by principles of respect and sustainability.

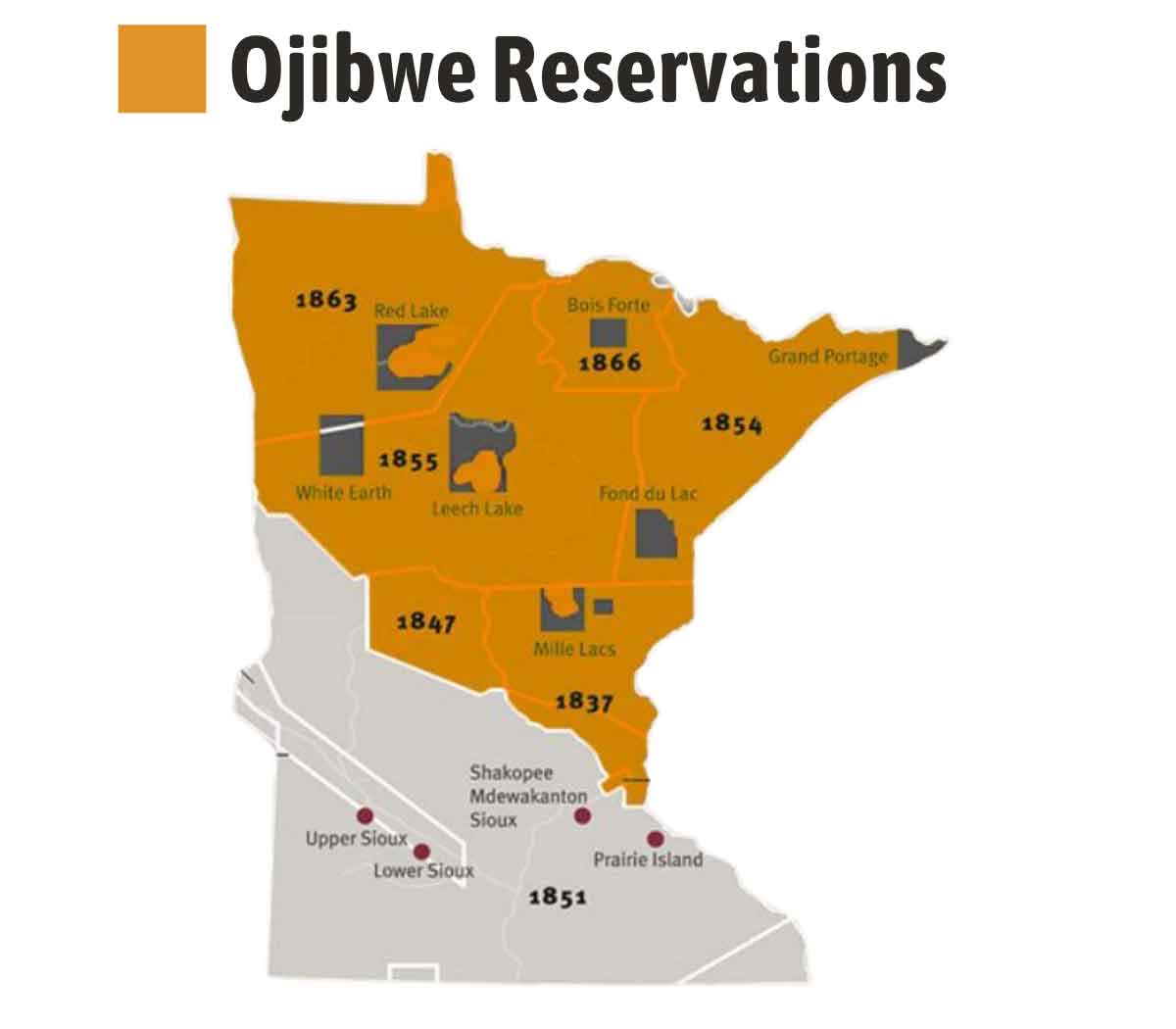

The arrival of European settlers and the subsequent formation of the United States dramatically altered this landscape. Through a series of treaties in the 19th century – notably those of 1837, 1854, and 1855 – the Ojibwe ceded vast tracts of land to the U.S. government. However, crucial to these agreements were the explicit reservation of certain "usufructuary rights," meaning the right to continue hunting, fishing, and gathering on the ceded territories. These were not rights granted by the U.S. government, but rather rights retained by the Ojibwe, rights they never relinquished.

"Our ancestors made sure these rights were in the treaties because they knew how vital fishing was to our survival and our way of life," explains Joseph Bear, an elder from the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe, his voice raspy with age and wisdom. "It’s not just about putting food on the table; it’s about who we are. It’s in our blood, our spirit."

These treaty rights, however, have not been without contention. For decades, state governments sought to assert their authority over tribal fishing, leading to a long history of legal battles and often tense encounters on the lakes. The landmark U.S. Supreme Court case Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians v. State of Wisconsin (1983), often referred to as the "Voigt decision," affirmed the treaty rights of Ojibwe bands in Wisconsin, setting a precedent that profoundly impacted Minnesota. While not directly involving Minnesota tribes, it paved the way for a clearer understanding and eventual recognition of similar rights in the state.

Today, seven federally recognized Ojibwe reservations dot Minnesota’s map: Bois Forte, Fond du Lac, Grand Portage, Leech Lake, Mille Lacs, Red Lake, and White Earth. Each band maintains its own natural resource department, developing and enforcing tribal regulations for fishing, often in coordination with state agencies, but always rooted in their inherent sovereign authority.

One of the most compelling examples of tribal sovereignty in action is the Red Lake Nation. Unlike any other reservation in Minnesota, the Red Lake Band did not cede its lands to the U.S. government through treaties. Instead, they retained nearly all of their original territory, including the vast Upper and Lower Red Lakes, which together form the largest lake entirely within Minnesota. This unique status means the Red Lake Nation has exclusive jurisdiction over its half-million-acre fishery, managing it without state interference.

The Red Lake fishery is a model of sustainable management. After a devastating collapse in the 1990s due to overfishing by both tribal and non-tribal entities (prior to exclusive tribal control), the Red Lake Nation implemented strict conservation measures, including a temporary closure of the walleye fishery and aggressive stocking programs. The results have been phenomenal. The walleye population rebounded, and Red Lake now supports a thriving commercial fishery, providing jobs and economic stability for the band members.

"We manage Red Lake like it’s our pantry," says a Red Lake Nation natural resource manager. "We understand that if we don’t take care of it, it won’t take care of us. Our management practices are guided by science, but also by our traditional teachings of respecting the resource for future generations." The Red Lake Nation’s success story stands as a powerful testament to the effectiveness of tribal self-governance in resource management.

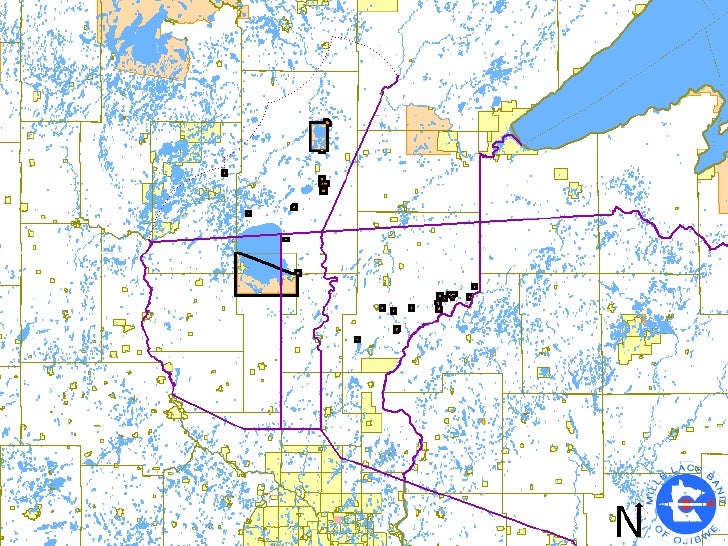

However, the path is not always as clear for other bands. The Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe, whose reservation abuts the famed Mille Lacs Lake, has faced significant challenges. While the lake is not entirely within reservation boundaries, the Mille Lacs Band, along with six other Ojibwe bands, holds treaty-reserved fishing rights in the lake’s ceded territory. This has led to the highly publicized "Walleye Wars," pitting tribal spear fishers and netters against recreational anglers and the state Department of Natural Resources (DNR).

The conflict often boils down to differing perceptions of fairness and resource allocation. Sport anglers, who contribute significantly to the state’s tourism economy, sometimes view tribal harvest as unfair competition, despite scientific data demonstrating that tribal harvests are carefully regulated and typically represent a small percentage of the total walleye mortality. The Ojibwe perspective is rooted in their inherent right, affirmed by treaties and court decisions, and their cultural imperative to harvest fish for sustenance and ceremony.

"It’s frustrating when people don’t understand that these aren’t special rights; they’re inherent rights, affirmed by solemn treaties," states Melanie Cloud, a Mille Lacs Band member and advocate for tribal treaty rights. "We’re not trying to take away anyone else’s fishing. We’re simply exercising our right to feed our families and practice our culture, just as our ancestors intended."

Beyond these high-profile conflicts, Ojibwe fishing communities grapple with a range of modern challenges. Climate change is altering lake ecosystems, impacting fish migration patterns and water temperatures. Invasive species, like zebra mussels, threaten native populations and water quality. Pollution from agricultural runoff and urban development also poses a constant threat to the health of the lakes.

In response, tribal natural resource departments are at the forefront of conservation efforts. They conduct their own scientific research, monitor water quality, operate fish hatcheries, and engage in habitat restoration projects. They often work collaboratively with state and federal agencies, seeking common ground in the shared goal of preserving Minnesota’s precious aquatic resources. These collaborations, however, are always underpinned by the assertion of tribal sovereignty, ensuring that Indigenous knowledge and priorities are central to the decision-making process.

The cultural significance of fishing extends far beyond the harvest itself. It is a vessel for intergenerational knowledge transfer. Elders teach youth about sustainable practices, the spiritual connection to the water, the Ojibwe language terms for fish and fishing gear, and the stories and ceremonies associated with the harvest. Fishing trips become classrooms, reinforcing cultural identity and strengthening community bonds.

"When I take my grandkids out on the lake, I’m not just teaching them how to set a net," says Elder Bear, looking out over Leech Lake. "I’m teaching them about respect for the Creator’s gifts, about our history, about their place in this world. I’m teaching them to be Anishinaabe."

The future of Ojibwe fishing in Minnesota is a complex tapestry woven with threads of tradition, science, sovereignty, and shared responsibility. While challenges persist, the enduring spirit of the Ojibwe people, their deep connection to the land and water, and their unwavering commitment to their treaty rights ensure that the nets will continue to be cast, the stories will continue to be told, and the vital current of their culture will flow for generations to come. The Ojibwe fishing tradition is not merely a relic of the past; it is a dynamic, living legacy, continually adapting, asserting its rightful place in the heart of Minnesota’s waters.