Guardians of the Sacred Cycle: The Enduring Power of Hopi Religious Ceremonies in Arizona

High above the vast, sun-baked plains of northeastern Arizona, perched precariously on ancient mesas, lie the villages of the Hopi people. For millennia, these resilient communities have been the custodians of a profound spiritual heritage, expressed most vibrantly through a complex calendar of religious ceremonies. Far from mere rituals, these ceremonies are the very pulse of Hopi life, intricate prayers for rain, fertility, and cosmic balance, enacted with a solemn reverence that speaks to an unbroken lineage stretching back thousands of years. In a world increasingly fragmented and secular, the Hopi continue to safeguard a living tradition, offering a rare glimpse into a holistic worldview where humanity, nature, and the divine are inextricably linked.

The Hopi, a Pueblo people, are believed to be descendants of the Ancient Puebloans (Anasazi) who once inhabited the Four Corners region. Their three mesas – First, Second, and Third Mesa – are among the oldest continuously inhabited settlements in North America, a testament to their deep connection to this arid, yet sacred, land. This connection is not merely geographical; it is spiritual and existential. The Hopi believe they were placed on this land by their creator, Maasaw, to be its caretakers, and their ceremonial cycle is the fulfillment of this sacred covenant.

At the heart of Hopi spirituality is the concept of Hopi Way, a philosophy emphasizing peace, humility, cooperation, and respect for all living things. Their ceremonies are not performed for personal gain or individual salvation, but for the collective well-being of their community and, indeed, all of humanity and the Earth itself. As one Hopi elder once articulated, "We are the caretakers of this land, and our ceremonies are our way of maintaining balance with the natural world." This profound sense of collective responsibility drives every song, every dance, and every prayer.

The ceremonial year is meticulously aligned with the agricultural cycle, particularly the cultivation of corn – the sacred staff of life for the Hopi. From the winter solstice to the late summer harvest, a series of elaborate ceremonies unfolds, each with a specific purpose, building upon the last to ensure the health of the community and the continuity of life.

Perhaps the most widely recognized, though often misunderstood, aspect of Hopi ceremonies involves the Katsinam (often Anglicized as "Kachinas"). These benevolent spirit beings, representing everything from ancestors and natural phenomena (rain, clouds, sun) to specific plants and animals, are central to the Hopi worldview. They are messengers, teachers, and bringers of blessings. During the ceremonial season, which typically runs from late December (Soyal) to July (Niman), masked male dancers embody these Katsinam, appearing in the village plazas to dance, sing, and distribute gifts to children.

The Katsina season begins with the Soyal ceremony around the winter solstice. This is a profound, introspective period focused on purification, renewal, and the turning of the sun. It’s a time for prayer sticks (pahos) to be made and offerings given, asking for blessings for the coming year and the return of the sun’s warmth. The Katsinam are formally invited to return to the villages, signaling the start of their active presence.

Following Soyal, the Powamuya (Bean Dance) ceremony, usually in February, marks a significant moment. Performed in underground ceremonial chambers called kivas, and sometimes in the plaza, it symbolizes the germination of seeds and the purification of the community. Young beans are grown in the warmth of the kivas, symbolizing the hope for a bountiful harvest. This ceremony is also a critical time for the initiation of children into the Katsina cult, where they learn the sacred meanings and responsibilities associated with these spirit beings. "The Katsinas come to teach us, to remind us of our responsibilities to each other and to the Earth," explains a Hopi cultural leader.

Throughout the spring and early summer, various Plaza Dances occur. These are the most visible expressions of the Katsina cycle, vibrant spectacles of color, sound, and movement. Dancers, adorned in meticulously crafted masks and costumes, embody specific Katsinam, moving with rhythmic precision to the beat of drums and the chant of ancient songs. Each dance carries a specific prayer – for rain, for strong crops, for health. While these public dances are often attended by respectful non-Hopi observers, it is crucial to remember they are not performances but profound acts of prayer and spiritual devotion. The energy generated by the dancers, combined with the collective prayers of the community, is believed to ascend to the spirit world, carrying their supplications.

The Katsina season culminates with the Niman (Home Dance) ceremony in July. This emotional and deeply significant event marks the departure of the Katsinam back to their spiritual home in the San Francisco Peaks. It is a bittersweet farewell, acknowledging their blessings and guidance throughout the growing season. The Niman often features elaborate dances and the distribution of more substantial gifts, including intricately carved Katsina dolls (tithu) for children, which serve as educational tools and representations of the spirits.

Beyond the Katsina cycle, other powerful ceremonies punctuate the Hopi year. The Wuwuchim ceremony, an initiation rite for young men, is a profound and lengthy process that traditionally occurred in the fall. It involves intense spiritual training, fasting, and the learning of sacred knowledge, marking a young man’s entry into full adulthood and his responsibilities to the community and its spiritual practices.

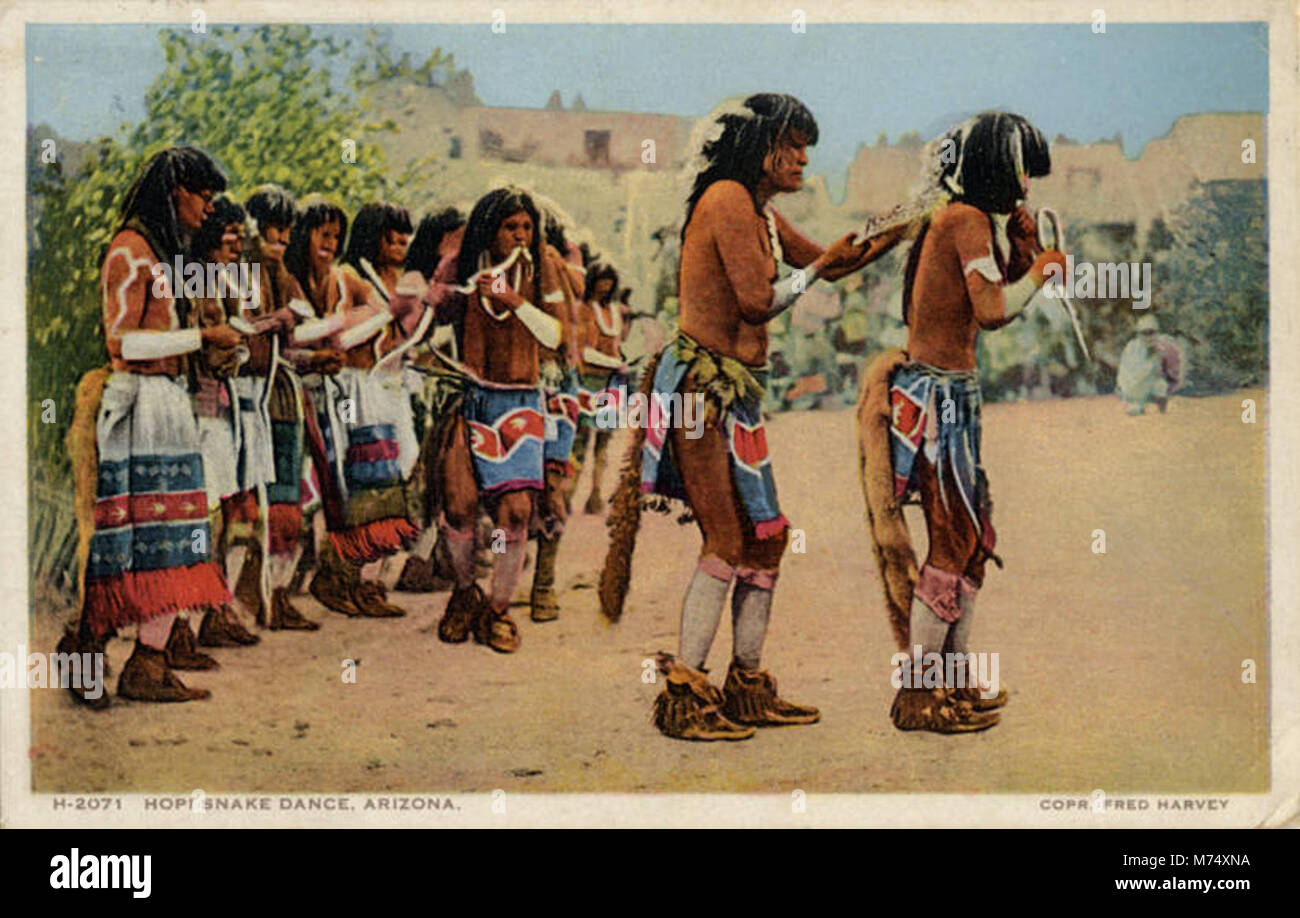

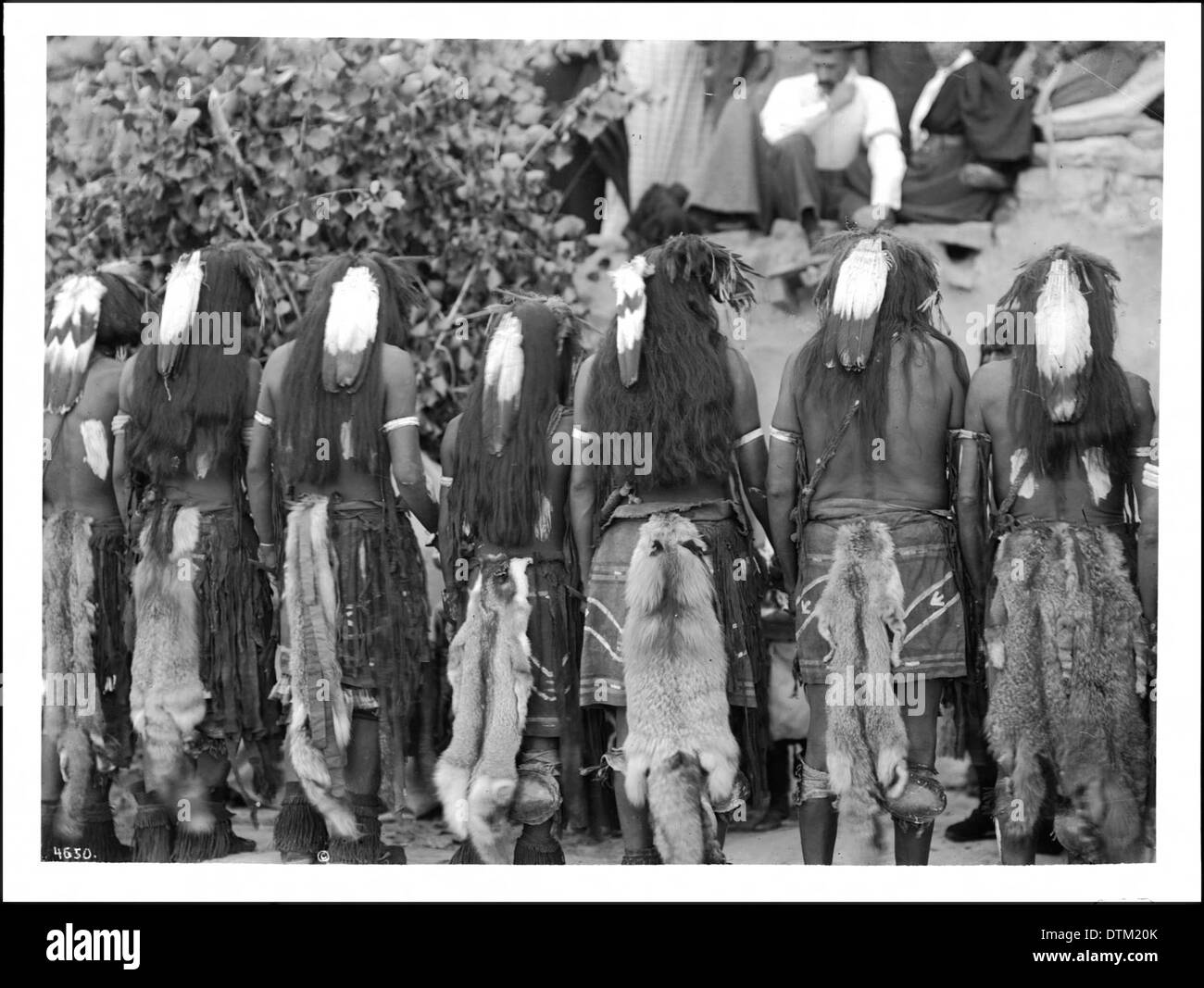

Perhaps the most famous, and certainly the most sensitive, of all Hopi ceremonies is the Snake Dance. Performed biennially in late August, alternating with the Flute Dance, it is an ancient and awe-inspiring plea for rain, involving the ritual handling of live snakes, including rattlesnakes. This ceremony is intensely private, highly sacred, and strictly closed to outsiders. Its fame has unfortunately led to much sensationalism and misunderstanding, prompting the Hopi to fiercely protect its sanctity and privacy. The respect for this boundary is paramount, as it underscores the Hopi’s right to cultural self-determination and the preservation of their most sacred practices from exploitation or misinterpretation. The power of the Snake Dance lies not in its spectacle, but in the profound courage, faith, and humility it demands of its participants, who willingly engage with dangerous creatures as living prayers to the underworld for rain.

The preparation for any Hopi ceremony is as significant as the ceremony itself. Days, sometimes weeks, are spent in the kivas, the subterranean ceremonial chambers that serve as sacred wombs of creation and transformation. Here, the spiritual leaders, or priests, engage in fasting, prayer, song, and the creation of sacred objects like prayer sticks and altars. These preparations are meticulous, precise, and deeply spiritual, ensuring that the ceremony is conducted with the utmost purity and intention. The kiva itself is a powerful symbol, representing the emergence place of humanity from the previous world, a connection to the ancestors and the Earth.

The continuity of these traditions relies on a robust system of intergenerational knowledge transfer. Children grow up immersed in the ceremonial cycle, learning the songs, dances, and meanings from their elders. While the public plaza dances are seen by all, the deeper, esoteric knowledge is passed down through initiation and apprenticeship, ensuring that the complex spiritual practices are maintained with accuracy and reverence. The entire community participates, whether as dancers, singers, drummers, cooks, or simply as devoted observers whose presence and prayer are integral to the ceremony’s efficacy.

In the modern era, the Hopi face significant challenges in preserving their religious ceremonies. The encroaching influences of the outside world, including mainstream culture, economic pressures, and the ever-present threat of cultural appropriation, demand constant vigilance. There is a delicate balance between sharing aspects of their culture respectfully and protecting the sacred core of their traditions from commodification or misrepresentation. Furthermore, climate change poses a direct threat to their rain-fed agriculture, making their prayers for rain even more poignant and urgent. The declining availability of water directly impacts their ability to cultivate the sacred corn, which is intrinsically linked to their ceremonial cycle.

Despite these pressures, the Hopi remain steadfast. Their ceremonies are not merely relics of the past but living, evolving expressions of their identity and their profound spiritual connection to the land and the cosmos. They are a testament to an enduring faith, a commitment to balance, and a powerful reminder of humanity’s potential for harmony with the natural world. To witness, even from a respectful distance, the dedication and reverence with which the Hopi carry out their religious ceremonies is to glimpse a timeless wisdom – a sacred cycle maintained not just for themselves, but for the health and well-being of all existence. Their mesas stand as beacons of cultural resilience, guardians of a spiritual path that continues to offer profound lessons in humility, interconnectedness, and the enduring power of prayer.