Guardians of the Land: The Resurgent Power of Tribal Parks and Recreation Areas

By

In the vast tapestry of North America’s protected lands, a unique and increasingly vital thread is being woven by Indigenous communities: Tribal Parks and Recreation Areas. Often overshadowed by the grandeur of national parks or the accessibility of state preserves, these sovereign-managed territories represent far more than just scenic vistas or recreational opportunities. They are living classrooms, sacred sanctuaries, economic engines, and bastions of cultural survival, demonstrating a profound and holistic approach to land stewardship that offers critical lessons for the entire planet.

From the majestic red rock formations of the Navajo Nation to the ancient forests of the White Mountain Apache, and the spiritual waters of the Great Lakes Anishinaabeg, Tribal Parks are distinct entities, born from a deep, intergenerational connection to the land. Unlike federal or state parks, their primary mandate extends beyond public recreation and conservation to encompass cultural preservation, traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), and the economic self-determination of their respective sovereign nations.

"Our land is not just a resource; it is our relative, our teacher, our identity," states a spokesperson for the National Congress of American Indians. "When we manage these lands, we are not merely preserving nature; we are preserving our heritage, our language, our ceremonies, and the very essence of who we are as a people." This fundamental philosophy underpins the management strategies of Tribal Parks, setting them apart and imbuing them with a distinct character.

A Legacy of Stewardship and Resilience

For millennia before European contact, Indigenous peoples were the original stewards of these lands. Their sophisticated systems of land management, developed over countless generations, included prescribed burns, sustainable hunting and gathering practices, and a deep understanding of ecological interconnectedness. The arrival of settlers, followed by forced removals and the establishment of reservations, severed many of these connections, but the knowledge and the spiritual bond endured.

The modern Tribal Parks movement is a powerful reclaiming of this ancestral stewardship. It represents a renaissance of Indigenous self-determination, where tribes are asserting their sovereignty not just over their people, but over their territories. This includes the right to manage and protect their natural and cultural resources according to their own values and laws.

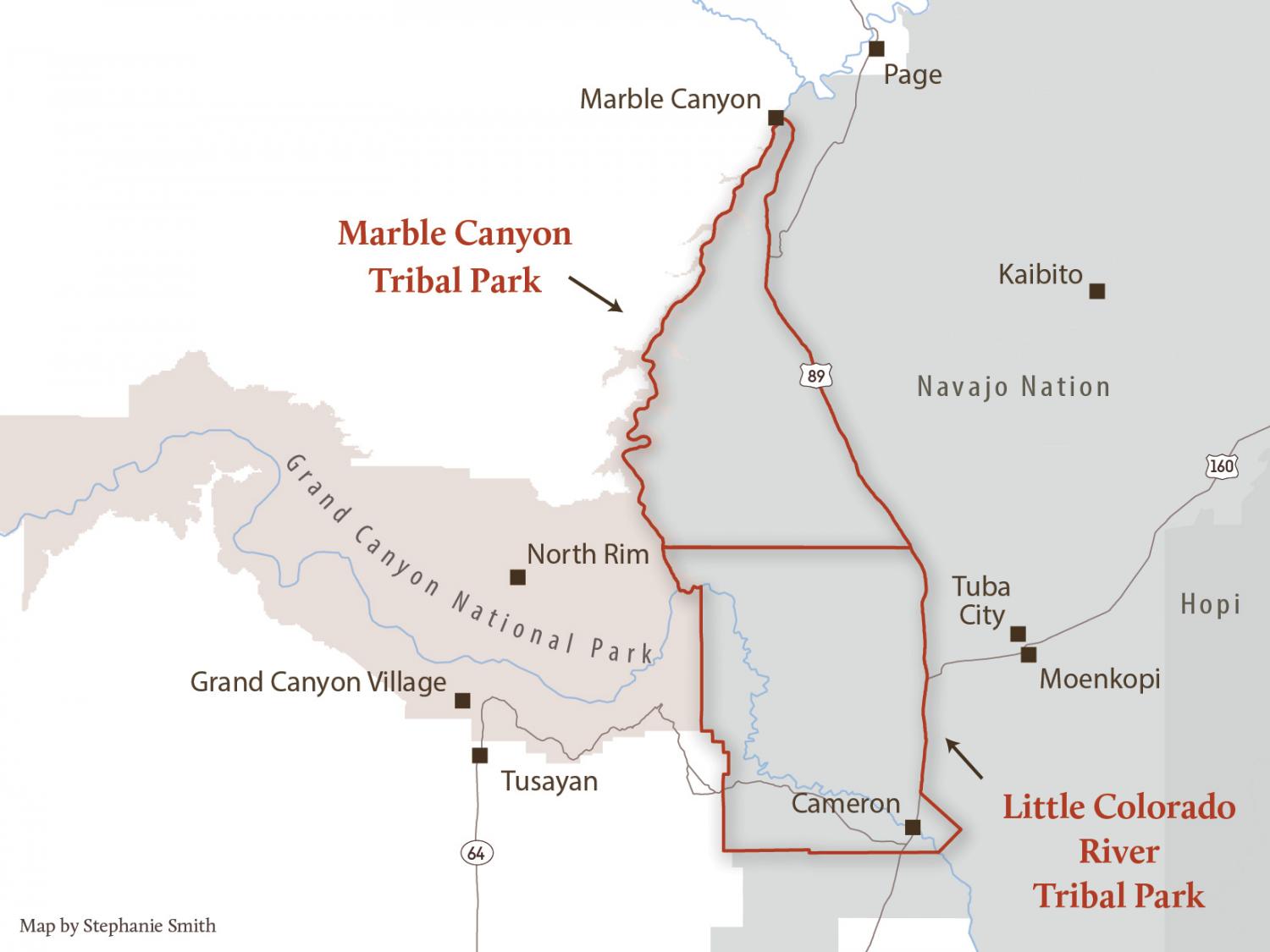

One of the most prominent examples is the Navajo Nation Parks and Recreation Department, which manages a sprawling network of parks, monuments, and recreation areas across its vast reservation in Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico. Iconic sites like Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park, Antelope Canyon, and Canyon de Chelly National Monument (co-managed with the National Park Service) draw millions of visitors annually. These parks are not only breathtakingly beautiful but are crucial for the Navajo economy, providing jobs, generating revenue for tribal services, and offering direct economic opportunities for Navajo guides and artists.

"When you visit Monument Valley, you’re not just seeing rocks; you’re seeing a landscape imbued with stories, with history, with the spirit of our ancestors," explains a Navajo guide. "Our tours are designed to share that connection, to educate visitors about our culture and our ongoing relationship with this land." This emphasis on cultural interpretation and immersive experiences is a hallmark of many Tribal Parks, offering a depth of engagement rarely found in conventional parks.

Beyond Recreation: Cultural Preservation and TEK

The heart of Tribal Parks lies in their role as centers for cultural preservation. They are places where traditional ceremonies are held, where sacred sites are protected from desecration, and where intergenerational knowledge is passed down. Elder-led programs often teach younger generations about traditional plant uses, hunting techniques, language, and the oral histories tied to specific landscapes.

The White Mountain Apache Tribe in Arizona, for instance, has long been recognized for its exemplary forest management practices. Integrating TEK with modern science, they have restored degraded forests, managed wildfires through cultural burning, and successfully reintroduced species like the Mexican wolf. Their Fort Apache Indian Reservation encompasses vast tracts of pristine wilderness, offering hunting, fishing, and camping opportunities while meticulously safeguarding sacred areas and archaeological sites. Their approach demonstrates that conservation can be more effective when guided by those who have lived in harmony with the land for centuries.

Another fascinating example is the Hualapai Tribe’s Grand Canyon West, home to the famous Skywalk. While controversial for its modern design, the Skywalk has provided an unprecedented economic boom for the tribe, allowing them to fund essential services, preserve their language, and maintain cultural programs. Critically, the Hualapai still retain vast areas of traditional lands within their reservation that are managed exclusively for cultural and ecological preservation, demonstrating a balanced approach to economic development and ancestral reverence.

Economic Engines and Self-Sufficiency

The economic impact of Tribal Parks cannot be overstated. For many tribes, these ventures are cornerstones of self-sufficiency, providing much-needed revenue in regions often characterized by limited opportunities. Tourism dollars directly support tribal governments, fund education, healthcare, and infrastructure projects, and create jobs for tribal members, reducing reliance on federal funding.

"We are building our own future, on our own terms," states an Oglala Sioux leader whose tribe is exploring developing eco-tourism initiatives around the Badlands. "Every dollar generated stays within our community, strengthening our sovereignty and allowing us to invest in what truly matters to our people." This direct feedback loop between land management and community well-being is a powerful model for sustainable development.

Challenges and the Path Forward

Despite their immense value, Tribal Parks face significant challenges. Funding remains a perpetual hurdle. Unlike federally designated parks, tribal parks often receive limited or no direct federal appropriations, relying heavily on self-generated revenue, grants, and sometimes partnerships. This disparity in resources can limit their capacity for infrastructure development, law enforcement, and comprehensive conservation efforts.

Jurisdictional complexities also arise, particularly when tribal lands border federal or state lands, leading to disputes over resource management, water rights, and wildlife corridors. Furthermore, the ongoing pressures of resource extraction industries (mining, drilling, logging) often threaten sacred sites and pristine ecosystems within or adjacent to tribal territories, forcing tribes into constant battles to protect their ancestral lands.

However, the resolve of Indigenous nations remains unyielding. They are increasingly forming coalitions, advocating for greater federal recognition and funding, and forging innovative partnerships with conservation organizations, universities, and even other governments. The concept of "Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas" (IPCAs) is gaining international traction, recognizing the unique and effective conservation outcomes achieved by Indigenous-led initiatives.

A Call for Recognition and Collaboration

As the world grapples with climate change, biodiversity loss, and the urgent need for sustainable practices, the wisdom embedded in Tribal Parks and Indigenous land stewardship offers invaluable solutions. Their holistic approach, which views humans as an integral part of nature rather than separate from it, stands in stark contrast to many Western models of conservation.

Visitors to Tribal Parks are not just tourists; they are guests invited to learn, to respect, and to witness a profound relationship between people and place. These visits offer opportunities to support Indigenous economies directly, to engage with diverse cultures, and to gain a deeper understanding of environmental ethics rooted in thousands of years of observation and practice.

In recognizing and supporting Tribal Parks and Recreation Areas, we are not only preserving some of North America’s most spectacular landscapes and vital ecosystems; we are honoring the sovereignty of Indigenous nations, fostering cultural resilience, and embracing a model of stewardship that holds immense promise for a more sustainable and equitable future. It is a powerful reminder that the true guardians of the land have always been, and continue to be, its original peoples.