From Alcatraz to Wounded Knee: The Fiery Dawn of Native American Civil Rights Activism

The 1960s and 1970s in the United States are largely remembered for the tumultuous civil rights struggles of African Americans, the anti-war movement, and the rise of counterculture. Yet, amidst these seismic shifts, another powerful, often overlooked, movement was gathering force – one that sought to reclaim sovereignty, dignity, and self-determination for the indigenous peoples of North America. This was the era of "Red Power," a period defined by audacious protests, armed standoffs, and a profound cultural reawakening that irrevocably altered the landscape of Native American rights.

For centuries, Native Americans had endured relentless policies of displacement, cultural suppression, and broken treaties. By the mid-20th century, federal programs like "Termination" and "Relocation" aimed to assimilate Native peoples into mainstream society, often at the cost of their land, culture, and communal identity. Termination policies, enacted in the 1950s, dissolved tribal governments and ended federal recognition, leading to the loss of millions of acres of tribal land and plunging many communities into deeper poverty. Relocation programs, meanwhile, incentivized Native Americans to move from reservations to urban centers, promising jobs and opportunities that rarely materialized, leaving many isolated and struggling in unfamiliar environments.

This backdrop of historical grievance and contemporary hardship fueled a growing sense of frustration and a burning desire for change. Young, educated Native Americans, many of whom had experienced both reservation poverty and urban alienation, began to organize, inspired by the direct action tactics of other civil rights movements.

The Birth of Red Power and Key Organizations

While smaller, regional groups had been active for years, the true spark of the national Red Power movement ignited with the formation of pivotal organizations. The National Indian Youth Council (NIYC), founded in 1961, was one of the earliest to advocate for "Red Power" and self-determination. They famously organized "fish-ins" in the Pacific Northwest, asserting treaty rights to fish in traditional grounds despite state regulations, leading to confrontations and arrests but drawing national attention to treaty violations.

However, the most visible and often confrontational face of the movement was the American Indian Movement (AIM). Founded in Minneapolis in 1968 by Dennis Banks, Russell Means, Clyde Bellecourt, and others, AIM initially focused on addressing police brutality and systemic discrimination against Native Americans in urban areas. They organized "survival schools" to educate Native youth in their culture and history, and patrolled streets to monitor police actions. But their ambitions quickly expanded to encompass broader issues of tribal sovereignty, treaty rights, and cultural preservation across the nation.

AIM’s methods were often provocative, designed to shock the public and force a reckoning with America’s treatment of its first inhabitants. They understood the power of media and spectacle to amplify their message.

Alcatraz: A Symbolic Reclamation (1969-1971)

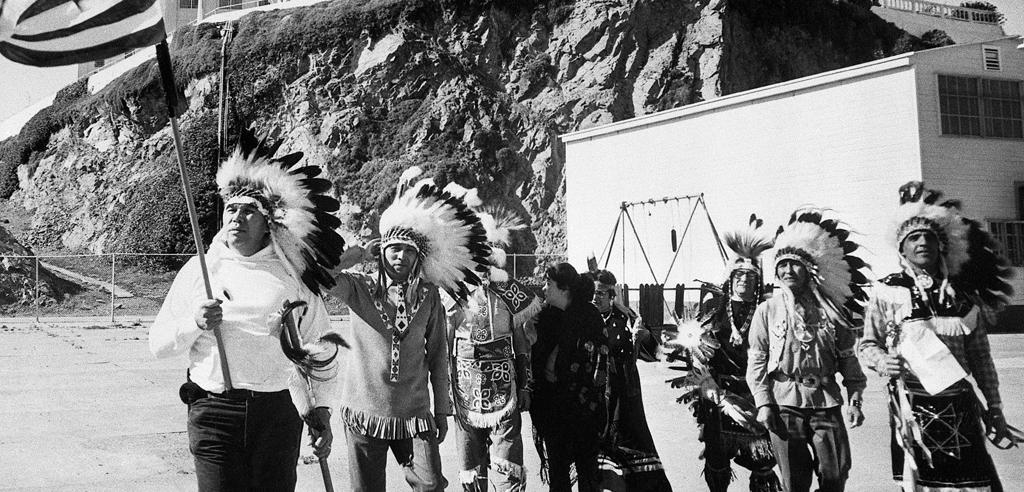

One of the movement’s earliest and most enduring symbols of defiance was the occupation of Alcatraz Island. On November 20, 1969, a group calling themselves "Indians of All Tribes" landed on the abandoned federal prison island in San Francisco Bay. Citing the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, which stated that all unused federal land should be returned to Native peoples, they claimed Alcatraz as theirs.

The occupation lasted for 19 months, capturing international headlines. Led by figures like Richard Oakes and John Trudell, the occupiers established a functioning community on the island, complete with a school, clinic, and broadcasting station. They issued a satirical declaration offering to buy Alcatraz for "$24 in glass beads and red cloth," mirroring the alleged purchase of Manhattan Island. Their demand was simple: the island should be developed as an Indian cultural center and university.

"We are not vanishing Americans," declared one Alcatraz communiqué, "but rather a nation of Indians who refuse to vanish." The occupation galvanized Native Americans across the country, inspiring pride and a renewed sense of collective identity. While the federal government eventually removed the occupiers in June 1971, the event had irrevocably shifted public perception and demonstrated the power of united Native action. It served as a powerful declaration that Native peoples were no longer content to be passive recipients of federal policy; they were active agents in shaping their own destinies.

The Trail of Broken Treaties and the BIA Takeover (1972)

Following Alcatraz, the movement gained momentum, leading to even bolder demonstrations. In the fall of 1972, AIM and other Native American groups organized the "Trail of Broken Treaties," a cross-country caravan from the West Coast to Washington D.C. The purpose was to highlight historical injustices, demand a re-evaluation of federal Indian policy, and present a 20-point position paper outlining their grievances and demands.

Upon arrival in Washington, the activists intended to meet with government officials. However, a breakdown in communication and a lack of adequate accommodations led to a standoff. On November 2, 1972, frustrated by perceived disrespect and broken promises, a group of activists occupied the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) building. For six days, they held the building, redecorating its walls with graffiti like "Red Power" and "Native Land," and appropriating files that they claimed documented government corruption and mismanagement of Native affairs.

The occupation ended with negotiations and an agreement for the government to review their demands. While the 20-point paper was never fully adopted, the BIA takeover was another dramatic assertion of Native American rights, exposing the systemic issues within the very federal agency tasked with Native affairs. It further solidified AIM’s image as a militant but effective voice for indigenous peoples.

Wounded Knee: A Siege for Sovereignty (1973)

The pinnacle of Red Power activism, and perhaps its most defining moment, came with the Wounded Knee Occupation in February 1973. Located on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, Wounded Knee was not just any site; it was the location of the infamous 1890 massacre where hundreds of unarmed Lakota men, women, and children were slaughtered by the U.S. Army. It was hallowed, tragic ground, chosen specifically for its potent symbolism.

The occupation began when approximately 200 Oglala Lakota, joined by AIM leaders and supporters, seized the village of Wounded Knee. Their primary demands were the reinstatement of the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty, which guaranteed the Lakota vast tracts of land and sovereignty, and the removal of the corrupt tribal chairman, Richard Wilson, who they accused of being a puppet of the federal government. They also sought to draw attention to the deplorable living conditions, violence, and lack of justice on the reservation.

The federal government responded with overwhelming force, encircling the village with U.S. Marshals, FBI agents, and armored personnel carriers. What ensued was a 71-day standoff, a modern siege complete with regular exchanges of gunfire. Two Native American activists, Frank Clearwater and Buddy Lamont, were killed by government fire, and several others were wounded.

Wounded Knee became a global media spectacle. Journalists flocked to the site, risking their lives to report from inside the occupied village, broadcasting the activists’ message to the world. It was a stark reminder of the long-standing conflict between Native Americans and the U.S. government, played out live on television. The occupation ended on May 8, 1973, with a negotiated settlement, though many of the promises made by the government were later reneged upon.

The legal aftermath of Wounded Knee was extensive, involving numerous trials, including those of Dennis Banks and Russell Means, which largely ended in acquittals or hung juries due to government misconduct. The legacy of Wounded Knee also includes the controversial case of Leonard Peltier, an AIM member convicted of the murder of two FBI agents during a shootout on Pine Ridge in 1975, whose continued imprisonment remains a rallying cry for human rights activists worldwide.

The Enduring Impact and Legacy

The Red Power movement of the 1960s and 70s had a profound and lasting impact. While it didn’t achieve all its immediate goals, it fundamentally reshaped federal Indian policy and ignited a powerful cultural resurgence.

One of its most significant legislative victories was the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975. This landmark legislation marked a pivotal shift away from the assimilationist policies of Termination. It allowed tribal governments to contract with the federal government to administer their own health, education, and other social programs, giving tribes greater control over their own affairs and resources. This act empowered tribes to pursue self-governance and economic development on their own terms, a direct outcome of the activism of the preceding years.

Beyond legislative changes, Red Power fostered a powerful sense of pride and identity among Native Americans. It inspired a new generation to reclaim their languages, spiritual practices, and cultural traditions. Universities began to establish Native American studies programs, and Native artists, writers, and musicians found new platforms for expression. The movement also laid the groundwork for future legal battles regarding land claims, water rights, and the protection of sacred sites.

However, the era was not without its challenges. Internal divisions within the movement, sometimes exacerbated by government infiltration and counterintelligence programs like COINTELPRO, led to infighting. The confrontations often resulted in violence, arrests, and the tragic loss of life, leaving deep scars within communities.

The Red Power movement of the 1960s and 70s was a raw, passionate, and often dangerous fight for justice. From the symbolic reclamation of Alcatraz to the armed standoff at Wounded Knee, Native American activists forced the nation to confront its historical injustices and acknowledge the inherent sovereignty of indigenous peoples. Their courage and tenacity laid the foundation for modern tribal self-governance, cultural revitalization, and an ongoing struggle for true equity and respect that continues to this day. The echoes of "Red Power" resonate as a testament to resilience, a demand for accountability, and an unwavering commitment to the future of Native nations.