The Shadow of Black Gold: The 1920s Conspiracy Against Oklahoma’s Oil-Rich Osage Nation

In the roaring 1920s, a decade synonymous with unprecedented economic boom and cultural liberation in America, a dark and insidious chapter unfolded in the heart of Oklahoma. Beneath the veneer of prosperity, a sinister conspiracy of greed, murder, and systemic exploitation targeted the Osage Nation, who, by a twist of fate and foresight, had become the wealthiest people per capita in the world. Their untold riches, derived from the vast oil reserves beneath their ancestral lands, did not bring security and comfort; instead, they attracted a predatory class of opportunists, lawyers, businessmen, and even family members, who saw the Osage as little more than obstacles to be removed.

This chilling saga, often dubbed the "Reign of Terror," is a stark reminder of the brutal realities of racial injustice and unchecked avarice that festered beneath the surface of American progress. It’s a story of how a nation’s legal and social structures could be twisted to dispossess a people of their wealth, their dignity, and ultimately, their lives.

The Unforeseen Riches: A Nation Transformed

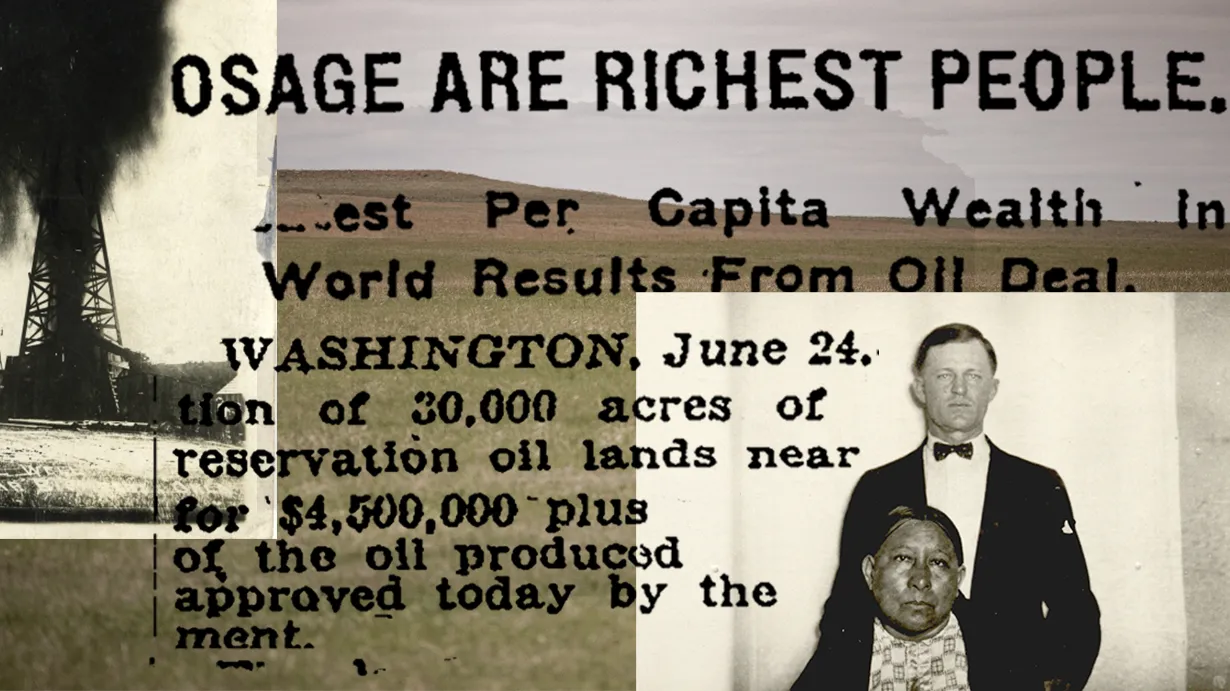

The Osage Nation’s journey to wealth was born from resilience and a shrewd negotiation. Forced from their ancestral lands in Kansas, they purchased a rocky, infertile reservation in northeastern Oklahoma in the late 19th century, a tract of land deemed worthless by many. Crucially, they retained the mineral rights beneath this land. When the geological bounty beneath the Osage Nation proved to be one of the largest oil fields in North America, their fortunes dramatically reversed.

By the 1920s, the Osage were receiving immense royalties from oil leases. Each enrolled Osage tribal member was entitled to a "headright," a share of the tribe’s mineral trust income. In 1923 alone, these headrights brought in an average of $13,000 annually per person – an astronomical sum at a time when the average American income was around $1,200. The Osage built opulent homes, drove luxury cars, and sent their children to elite boarding schools. They had transcended poverty, but their newfound prosperity came with a deadly price tag.

The Guardianship System: A Legal Loophole for Plunder

The very system intended to "protect" the Osage from exploitation became its primary instrument. In 1906, Congress passed legislation that declared many Osage "incompetent" to manage their own finances, despite many being fully capable, educated individuals. This paternalistic and inherently racist policy mandated that a white "guardian" be appointed by local courts to manage the financial affairs of any Osage deemed "full-blood" or otherwise "incompetent."

These guardians, often local businessmen, lawyers, or even barbers, were given complete control over the Osage’s vast wealth, theoretically for their ward’s benefit. In practice, the system was rife with corruption. Guardians routinely embezzled funds, overcharged for services, and manipulated their wards’ accounts. Probate courts, intended to oversee these arrangements, were often complicit, approving fraudulent transactions with little scrutiny. This legal framework created a direct pipeline for white opportunists to siphon off Osage wealth, but it was not enough for the most ruthless among them. They wanted the headrights themselves, which meant the Osage owners had to die.

The Reign of Terror Begins: A Spate of Mysterious Deaths

The mysterious deaths began subtly, almost unnoticed at first, in the early 1920s. Osage tribal members, especially those with significant headrights, started dying under suspicious circumstances. Some were poisoned, others shot, their homes bombed, their cars found crashed with no survivors. The local authorities, predominantly white and often tied to the very individuals benefiting from Osage exploitation, were either inept, complicit, or actively obstructed justice.

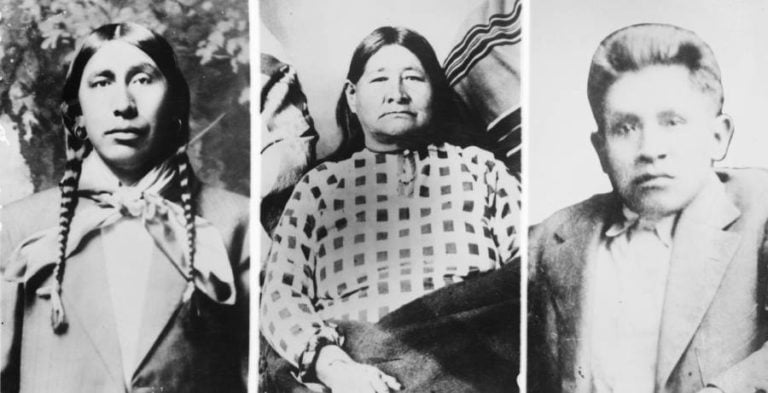

One of the most prominent families targeted was that of Mollie Burkhart, an Osage woman with significant headrights. Her sister, Anna Brown, disappeared in May 1921, only to be found days later, shot execution-style in a remote ravine. Months later, her mother, Lizzie Q., died under suspicious circumstances, believed to be poisoned. Then, in 1923, Mollie’s sister Rita Smith and her husband Bill were killed when their home was bombed, a powerful explosion that rattled the entire town of Fairfax. Mollie herself later fell gravely ill, believed to be suffering from a slow-acting poison administered by her own husband, Ernest Burkhart.

The cumulative effect of these murders was a palpable atmosphere of terror and paranoia within the Osage Nation. No one knew who to trust. Funerals became grim social events, with families fearing they might be next. The body count steadily rose, with estimates ranging from two dozen to over a hundred Osage deaths linked to the conspiracy, many never fully investigated or officially attributed to foul play.

William K. Hale: The "King of the Osage Hills"

At the center of this web of deceit and murder was William K. Hale, a seemingly benevolent cattleman and businessman who styled himself the "King of the Osage Hills." Hale was charismatic, influential, and deeply integrated into the local community. He cultivated friendships with the Osage, lent them money, and even participated in tribal ceremonies. But beneath his charming façade lay a ruthless, calculating mind driven by an insatiable hunger for wealth.

Hale systematically orchestrated the murders of Osage individuals whose headrights he coveted. He employed a network of accomplices, including his nephew Ernest Burkhart (who married Mollie), local criminals, and even a corrupt doctor who administered poisons. Hale’s strategy was chillingly simple: eliminate the headright holders, and through marriage or other means, ensure the headrights passed to his co-conspirators, ultimately under his control.

The Federal Investigation: A Nascent FBI Steps In

The local authorities’ failure to act, coupled with the sheer volume and brazenness of the killings, eventually drew the attention of the federal government. The Osage Nation appealed directly to Washington, D.C., and in 1925, J. Edgar Hoover, then director of the fledgling Bureau of Investigation (BOI, later the FBI), dispatched a team of undercover agents to Osage County.

Leading the investigation was Tom White, a former Texas Ranger known for his tenacity and integrity. White assembled a diverse team, including a Native American agent and others who blended into the community, posing as cattle buyers, insurance salesmen, and prospectors. They faced immense challenges: a deeply distrustful Osage community, a corrupt local establishment, and a landscape of fear where witnesses were intimidated or murdered.

The agents meticulously gathered evidence, piecing together a complex puzzle of lies, alibis, and betrayals. Their breakthrough came through persistent detective work, informants, and eventually, the confession of one of Hale’s hitmen, Kelsie Morrison, who implicated Hale and Ernest Burkhart in the murders.

Justice, Albeit Imperfect

The federal investigation led to the arrests and trials of William K. Hale, Ernest Burkhart, and several of their accomplices. The trials were sensational, capturing national headlines. Ernest Burkhart eventually turned state’s evidence, testifying against his uncle. In a landmark case for the nascent FBI, Hale and Burkhart were ultimately convicted of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment. Others received lesser sentences or were never brought to justice.

While the convictions offered a measure of relief and demonstrated the federal government’s capacity to intervene where local justice failed, they did not fully heal the deep wounds inflicted upon the Osage Nation. Many murders remained unsolved, and the systemic issues that enabled the exploitation, particularly the guardianship system, persisted for years, albeit with some reforms. The trauma of the "Reign of Terror" cast a long shadow over generations of Osage families.

Legacy and Remembrance

The 1920s Osage murders represent a pivotal, yet often overlooked, chapter in American history. It exposed the raw brutality of racial prejudice, the corrosive power of greed, and the systemic failures that allowed such atrocities to occur. The case also marked a significant early success for the Bureau of Investigation, cementing its reputation as a formidable federal law enforcement agency.

Today, the story of the Osage "Reign of Terror" has gained renewed prominence thanks to David Grann’s meticulous 2017 non-fiction book, Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI, and its subsequent film adaptation by Martin Scorsese. These works have brought this vital history to a global audience, highlighting the resilience of the Osage people and ensuring that their suffering, and the injustice they faced, will not be forgotten.

The Osage Nation continues to thrive, having meticulously rebuilt and maintained its sovereignty and cultural identity. They have established their own tribal courts and government, and continue to manage their mineral estate with great care. The painful lessons of the 1920s serve as a powerful reminder of the importance of self-determination, the dangers of unchecked power, and the enduring fight for justice in the face of historical injustices. The black gold beneath their feet brought both unimaginable wealth and unspeakable terror, a duality that forever etched their story into the complex tapestry of American history.